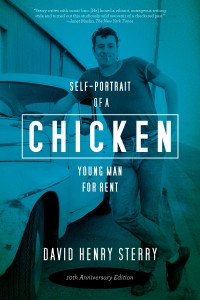

To commemorate the publication of the 10 year anniversary edition of my memoir Chicken Self:-Portrait of a Man for Rent, I have decided to do a series of interviews with memoirists I admire. I’ve known Sherril Jaffe for many years. Not only is she a brilliant writer, she’s also an amazing teacher of writing. She is a tenured professor at Sonoma State University, has won a 2001 PEN award and was a 2010 MacDowell Fellowship. She is the author of many books, novels, short stories, poetry and yes, a memoir.

David Henry Sterry: Why in god’s name did you decide to write a memoir?

Sherril Jaffe: When she was fifteen, my older daughter became rebellious and ran away from home. My husband and I were terrified and mystified by her behavior. Advice and blame came at us from every direction, and we didn’t know what to do, so finally I began to do what I have always done in order to process experience; I began to make narratives out of what was happening. I thought if I could do this well enough that she would read it and understand my concerns for her and how much I loved her and she would stop acting in ways that created so much anxiety for me. I was writing a letter to her and I was also managing my anxiety by giving form to it. Toward the beginning of what became Ground Rules, my agent sold the book on proposal. Selling the book validated my attempts to take the straw of each day and weave it into gold each night, to give form to the chaos we were experiencing. If I could do this, I thought, I might be able to grasp what was happening so I could address it. We were all suffering, and I wanted the suffering to end. I was now writing a book, and books have ends. I had set up things so I would have help getting it right—acquiring an editor when I sold the book. Other people with teenager crises were relying on counselors. I had tried that without success, so now I was banking on my editor.

Sherril Jaffe: When she was fifteen, my older daughter became rebellious and ran away from home. My husband and I were terrified and mystified by her behavior. Advice and blame came at us from every direction, and we didn’t know what to do, so finally I began to do what I have always done in order to process experience; I began to make narratives out of what was happening. I thought if I could do this well enough that she would read it and understand my concerns for her and how much I loved her and she would stop acting in ways that created so much anxiety for me. I was writing a letter to her and I was also managing my anxiety by giving form to it. Toward the beginning of what became Ground Rules, my agent sold the book on proposal. Selling the book validated my attempts to take the straw of each day and weave it into gold each night, to give form to the chaos we were experiencing. If I could do this, I thought, I might be able to grasp what was happening so I could address it. We were all suffering, and I wanted the suffering to end. I was now writing a book, and books have ends. I had set up things so I would have help getting it right—acquiring an editor when I sold the book. Other people with teenager crises were relying on counselors. I had tried that without success, so now I was banking on my editor.

I worked on the end of the book endlessly, tinkering and tinkering. My editor was rigorous, however, and wouldn’t accept anything that didn’t really ring true. But then finally the true ending appeared—everything begins to turn around finally when the parents learn to see, respect, and support their daughter for who she actually is, rather than who they have wished, assumed or feared that she was.

I speak here of “the parents” instead of “me and my husband,” because as a fiction writer it is difficult for me to think of a character based on me as me. I had sold the book as a memoir but I didn’t give much thought at the time as to what that really meant. I was very afraid for my daughter and eager for this situation to resolve. Unusually for memoir writers, I was writing as the situation was unfolding. The consensus of opinion is that the more distance you have on your material, the better chance you have of getting a proper handle on it, but I couldn’t afford the luxury of waiting for my material to age like a fine wine; my daughter’s life was on the line. As I worked, I kept wishing I could peek ahead to the end of the book to see how things were coming to turn out. I called what I was working on “The Uncertainty Principle” after Heisenberg’s discovery that the act of observation changes the measurement of what is being observed. I could not take any of the draconian measures some were advising us to adopt with our daughter: all I could do to effect a change eisenberg’s fin our circumstances was to observe them as closely as possible, distill and transform them until their meaning was revealed and we were all saved.

DHS: What were the worst things about writing your memoir?

SJ: The worst thing about writing my memoir was that I did not know if there was going to be a happy ending. Although I was the author, every time I attempted an ending that was one that I wanted but which wasn’t exactly true, it wouldn’t work artistically; my editor would catch it, and I would be sent back to the drawing board. Meanwhile our struggle with our daughter resolved just as, in the book, the parents come to see and love their daughter for who she really is, and that is where the story ends.

DHS: What were the best things about writing your memoir?

SJ: Since I was writing my memoir— though not in letter format—as a letter to my daughter, it gave me a way to try to reach out to her who had become so mysteriously distant, so I felt I was doing what I could to keep her safe and to stay connected with her.

DHS: Did writing your memoir help you make some order out of the chaos we call life?

SJ: Indeed, it was my only defense against the chaos. I was also trying to shape the narrative as I went toward a happy ending, trying to make happiness the inevitable outcome of the story, for there are endless possibilities in chaos.

DHS: How did you make a narrative out of the seemingly random events that happened to you?

SJ: There was no problem, since I believed the book was simply being delivered to me, chapter by chapter, and that though the events transpiring seemed random, the work of bringing the book into being was the act of discovering in what way the events were actually not random at all.

DHS: How was the process of selling your memoir?

SJ: I had recently signed up with an agent I loved, so I was not surprised that she sold the book on proposal in short order. There was some suspense as to what the offer would be, and I was disappointed that it was only $15,000, but, on the other hand, knew that $15,000 was the inevitable figure, for at that time I had a magical calendar, and the picture for that month was a painting by Charlie Demuth of a target with one five in the bull’s eye, one in a middle ring and another on the outer band. They offered me five thousand upon signing, five more when I handed in the manuscript and a final five upon publication.

DHS: How did you go about promoting and marketing your memoir?

SJ: Very poorly! However, I don’t think it was entirely my fault. The publisher rejected my title, “The Uncertainty Principle” and made me call the memoir “Ground Rules,” and so the public misunderstood what the book promised. The public expected this to be a guide to controlling teenagers by doing concrete things, like grounding them, for example, not a testament to living with uncertainty.

DHS: Did you have difficulty speaking in public about the intimate aspects of your memoir?

SJ: No; I have never had a problem speaking in public about anything; my problems came from people speaking to me in private—people I didn’t even know feeling it was okay to give me their opinions about me and my daughter. I was used to people giving me a critical response to my writing but not to me, personally. This was a shock. I vowed to never again write another memoir.

DHS: How did your family, friends and loved ones react to your memoir?

SJ: I know now that it was very hard on my daughter, being in the public eye, like that, and I very much regret any pain I may have caused her. But the plain fact is, the story was written with great love, solely with the intention of keeping her safe by daring to look closely at the terrible reality of life, for nothing looked at squarely can hurt you. And our troubles did end—whether because of the effect of the book on reality or because, like a virus, they had run their course.

DHS: I hate to ask you this, but you have any advice for people who want to write a memoir?

SJ: Yes. My advice is, watch out, unless you are an extrovert and the point for you is to have everybody talking about you, passing judgments about you and projecting onto you. It feels good when you are admired, of course, but I’m a writer, not a model; I would rather it was my work, not my person, that was getting the attention. I felt invaded, and it made me queasy when readers I had never met believed they were intimate with me.

David Henry Sterry is the author of 16 books, a performer, muckraker, educator, activist, and book doctor. His new book Chicken Self:-Portrait of a Man for Rent, 10 Year Anniversary Edition, has been translated into 10 languages. He’s also written Hos, Hookers, Call Girls and Rent Boys: Professionals Writing on Life, Love, Money and Sex, which appeared on the front cover of the Sunday New York Times Book Review. He is a finalist for the Henry Miller Award. He has appeared on, acted with, written for, been employed as, worked and/or presented at: Will Smith, a marriage counselor, Disney screenwriter, Stanford University, National Public Radio, Milton Berle, Huffington Post, a sodajerk, Michael Caine, the Taco Bell chihuahua, Penthouse, the London Times, Edinburgh Fringe Festival, a human guinea pig and Zippy the Chimp. He can be found at www.davidhenrysterry.com.