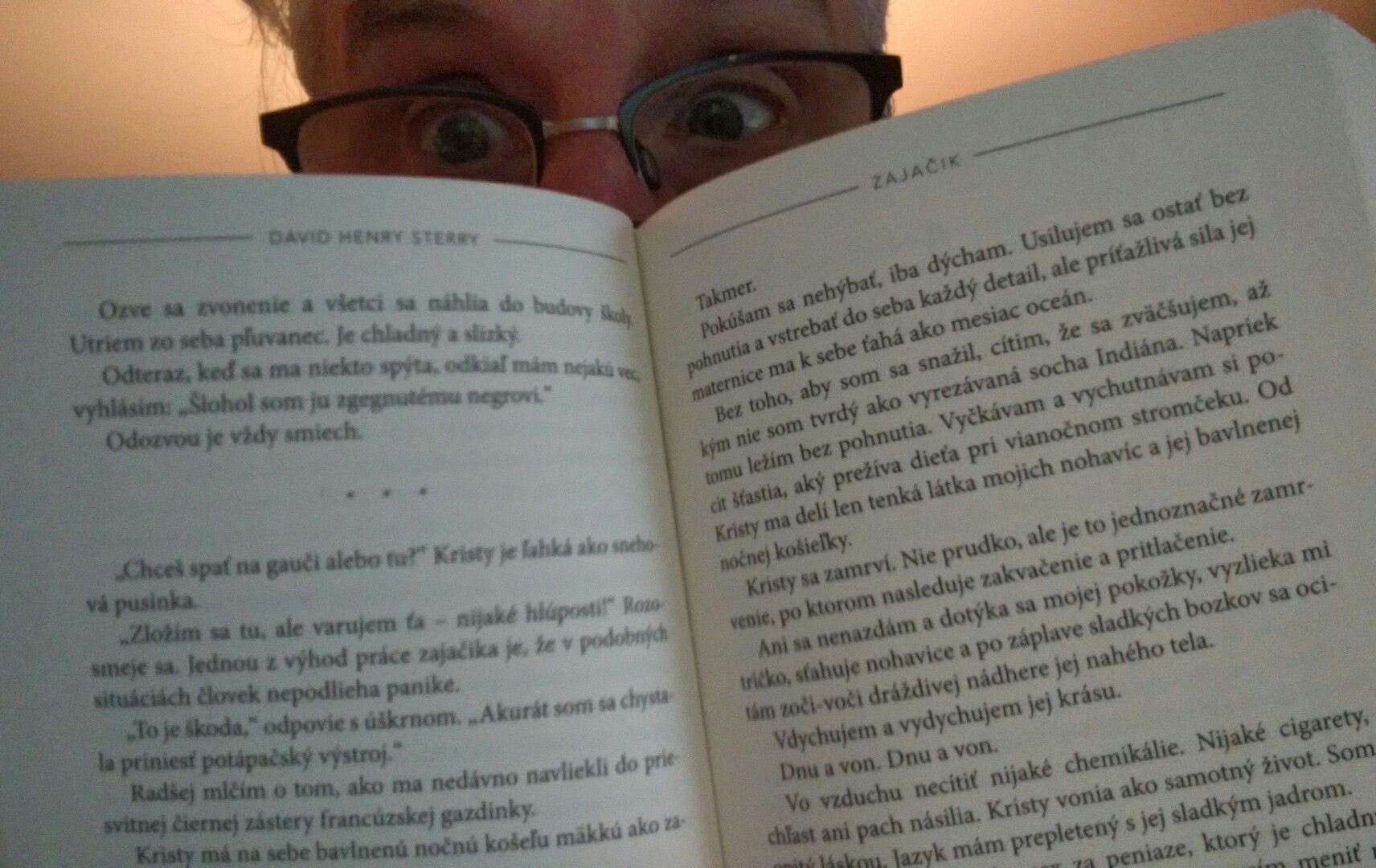

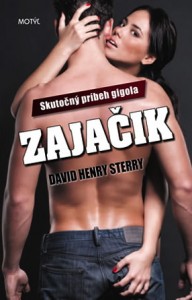

Just got copies of the Slovakian translation of Chicken. Here’s a sample.

Month: May 2016

We live in Montclair, New Jersey. John Dufresne lives in southern Florida. So naturally, we met him at the South Dakota Festival of Books. We were sitting next to him waiting for people to show up to sign our books. Let’s just say there wasn’t a huge line. Normally, this would really be a downer, but this time we realized it was good luck because we got the chance to talk with John.

John has had a long and distinguished career as a writer. He also teaches writing. Now that his new book, I Don’t Like Where This Is Going, is out, we picked his brain about writing, books, publishing, and life.

To read the full interview on the Huffington Post, click here.

The Book Doctors: When did you first start becoming a writer, and how did you learn to be one?

John Dufresne: I was a storyteller first, even if I didn’t know I was. My father told me a bedtime story every night. Fairy tales. Only I thought he made them up because he had no book. I thought he invented wolves. He may be why I loved stories and wanted to make up my own. I had a couple of narratives going when I was seven or eight or so in which I was the central character. They both took place in my neighborhood. In one I was the leader of a band of good guys with white hats and spirited horses. Cowboys on Grafton Hill in Worcester, Mass. The only real horse we ever saw on the Hill was the ragman’s nag, whom we loved to pat. Every night in bed I continued the story from where it ended when I had dozed off the night before. I did this for years. And during the day, I was thinking of what I would now call plot points and creating new characters. The other narrative was similar with me as a sports hero. Whenever I heard sirens, I imagined the house the fire trucks were heading for and the people trapped inside the burning house and how they would be saved. Or not.

TBD: What were some of your favorite books as a kid, and why?

JD: I grew up in a house without very many books. We did have 26-volumes of the Universal Standard Encyclopedia, bought for 99 cents a week at the A&P on Grafton Street. I read them in order, not quite thoroughly. One month every subject I talked about at the supper table began with A. Afghanistan, alligator, antbirds. With volume 13, it was everything between Idaho and Jewel Cave. I loved information, loved knowing the names of things. I didn’t much like the stories we read in my grammar school, stories about kids who had horses and good fortune. I couldn’t find anyone like me, someone who grew up in a housing project, in them. Then I happened on a series of books that I devoured, the Chip Hilton series for boys, written by Claire Bee. I think it was David Mamet who described drama as two outs, bottom of the ninth, man on first, 3-2 count, and your team down by one. That describes Clutch Hitter, a book in the series that illustrated to me, the little jock that I was, how exciting, compelling, and tense a story could be.

TBD: Your new book, I Don’t Like Where This Is Going, is a wild, wacky ride that fits squarely into the noir tradition, but it seems to break as many rules as it follows. How did you get the idea for the book, and does writing in this genre inform how you work?

JD: I found a character I liked in a short story I wrote. I wrote the story, my first bit of crime fiction, on request. The character was Wylie Melville, a therapist and police consultant; the story was “The Timing of Unfelt Smiles,” and it appeared in Miami Noir and in Best American Mystery Stories 2007. I wanted to give Wylie a much larger problem to solve and to put his life in great danger. That’s what got me started, that and the long legacy of police and political corruption in South Florida, rich material to work with. Then, having done it once, I thought, I’ll do it again. I liked Wiley and Bay and wondered what mayhem would follow them and where would they go. They went to Vegas so that Bay could ply his trade at the poker tables. To be honest, I hadn’t read much crime fiction before I wrote crime fiction. Sherlock Holmes, of course, books my friends Les Standiford, James W. Hall, and Dennis Lehane wrote. So if I broke any rules, I may not have known what they were. I wrote the two novels like I wrote every book with the focus on characters and themes, not on plot. This is what it means to be a human being and this is how it feels.

TBD: What do you want people to take away from your novel?

JD: Before I was a writer, and before I was a house painter, I worked for a while in social service organizations, a suicide prevention hotline, like the one Wylie works at in Vegas, a youth center, a drug prevention program. So I was in touch with that difficult life that so many people have here. In America. I worked with so many people who had lost hope and others who were in terrible emotional pain. And I’ve never lost that feeling that we don’t do enough to take care of the less fortunate. The exploitation and oppression of unfortunate people is something I’d hope the reader would think about. Daily violence is a norm here, but it’s easy to look the other way. And I want the reader to care about Wylie and his friends.

TBD: What were some of the pleasures and perils of writing this book?

JD: I spoke glibly above saying how theme and character drove the novel. Plot’s always been the most difficult aspect of novel writing for me. It’s so damn hard. So when I wrote the first Coyote novel, I got to about 250 pages when I realized I didn’t know who committed those murders in the opening chapter, and I thought, this is why the crime writers make the big money: they have to write a novel and solve a crime. Too late then to bring a bad guy with a gun onto the stage. So it was pack to page one. Same thing this time. As possible suspects entered the novel, I paid attention and watched them looking for clues. Anyone of them could have done the deed, but who really did? Wylie’s no Sherlock Holmes, no consulting detective, but he is a man who pays attention. And he doesn’t work alone. He has the illusionist Bay and the bedlamite Open Mike by his side.

TBD: Tell us about how you got your first book published?

JD: It was a book of short stories, and I had probably published six or seven stories in literary journals. I had a bunch of others, and I put them together as a book, and I went through one of those books Writer’s Digest put out or something like that. And I looked through all of the agents looking for short story collections, and there were three.

TBD: I’m surprised there were three!

JD: I know, I know! So I wrote to the three of them, and one of them got back to me. He was very enthusiastic. I would tell anybody who is looking for an agent, make sure the agent is excited about you and your project. Not just, “I’ll do it…” Because it’s hard for an agent to sell a book. Especially if it’s short stories. So my agent sent my book of stories around for about a year. It finally sold to Jill Bialosky at Norton, and I’ve been with Jill and Norton ever since. I remember my editor saying, “You’re the last guy I’ll ever sell a book of stories for.”

TBD: Your career is interesting and highly unusual for today in terms of sticking with one publisher for each book. And it’s a publisher that’s independent but has real chops in this business. Not to mention the fact that you write very quirky books that are not highly commercial, mainstream, etcetera. How can other writers achieve this kind of elusive success?

JD: First of all, the best readers you’re going to get are your agent and your editor. They’re generous. They want your book to succeed. And they know what they’re talking about. Even if you disagree with them, I always say, just do what they tell you to do. Because they know the business. I don’t know anything about the business. I don’t want to know; I want to write. I also say, if you write something beautiful and moving and telling, it’ll get published. But it may not get published when you want it to be, or where you want it to be. The important thing for a lot of young writers is getting it published. I steer them away from self-publishing. Some of them have, and that’s alright. But you want to get the imprimatur of somebody else. Somebody else who believes in you. Small presses are as good a place to be published as large presses… I mean obviously you’re not getting the same money. But the money isn’t like it was before. You used to be sent on book tours. Now you’re lucky if they give you lunch money. The important thing is to get yourself into the game. You get your book around. You have people reading it. Just don’t give up. You owe it to your characters that you love to get other people to read about them. Until you get an agent, you’re going to do the business work too, and persist with it. I think in some ways publishing is more democratic than it ever was.

TBD: When we go to these conferences, there’s always one person who’s telling writers, “You have to be on Facebook! You have to be on Twitter! You have to have a website, blah blah blah-” And you can see the blood draining out of writers’ faces.

JD: The publishers want you to do work with them, which I understand. When I did my first book of stories, I set up what I called the Motel Six tour. I told them, “Get me the books and a bookstore, and I’ll drive. I’ll take my wife and my kid, and we’ll drive to all the bookstores.” And that’s what I did. And they were all really happy, because this was before social media. I printed up a fake newspaper from Louisiana Power and Light, and Norton sent it around, and got hard copies to people. It was fun. They appreciated that I was willing to do it. I still do it. Somebody just asked me to do a bookstore in Baltimore. But I’m thinking, “How much is this going to cost me?” In the old days, they put me up in beautiful hotels. Paid for everything. Now, at least for mid-list people like me, it’s not happening. And I don’t think it’s happening too much in general anymore. I also have gotten on Facebook because Norton said to do that. A guy helped me out. My wife is good at the computer. I think that’s been kind of helpful. It’s a nice way to spread the news. I saw there was a good review of my new book in the Tampa Bay paper on Sunday, and I put it online. Lots of people have liked it already. They know about the book, they buy the book. Twitter I’ve never been on. I remember once, Carol Houck Smith (who was an editor at Norton for years) and I were sitting together by these editors, and they were all answering questions with, “You need a platform.” And Carol muttered under her breath, “I don’t need a goddamn platform, I need a great book!”

TBD: What are you reading now?

JD: I tend to read a lot of books at the same time. I’m reading Lee Martin’s new novel Late One Night, which begins with the death of a mother and three kids in a fire that may or may not have been arson. And I started Campbell McGrath’s new poetry collection, XX, in which he writes a poem for every year in the last century, in the voices of some of the century’s prominent figures, like Picasso. Mao, and Elvis. Also reading Wired to Create, by Kaufman and Gregoire, and Actual Minds, Possible Worlds by Jerome Bruner. I’m loving, if not completely understanding, Lawrence M. Krauss’s A Universe from Nothing and Carlo Rovelli’s Seven Brief Lessons on Physics.

TBD: How does teaching fiction help or hinder you as a fiction writer?

JD: It only helps. Every reading and every discussion of a story helps me see how stories work or don’t work, including my own. We’re all apprentices in a craft where no one is a master–I think Hemingway said that. This is the craft so long to learn. I always feel better at the end of class than at the start. I always feel like rushing home (which is actually impossible on Biscayne Boulevard) and getting back at whatever it is I’m writing. To be honest, there are moments that I would rather be learning about my central character’s secrets than reading a story about goblins with swords, but I know I’ll learn something about setting a scene, let’s say, in the goblin story that will be valuable to my students and to me.

TBD: We hate to ask you this, but since you actually wrote a book about how to write a novel, we feel we have to. What advice do you have for writers?

JD: Probably the advice you were expecting to hear: read and write every day. No holidays for the writer. We always find time to do the things we love. We only have to want to write as much as we want to go to the movies. And if you don’t love writing and reading, do something else. It’s too hard, and discipline won’t bring you to the writing desk. Only love for stories will do that. Here’s Faulkner on reading: “Read, read, read. Read everything — trash, classics, good and bad, and see how they do it. Just like a carpenter who works as an apprentice and studies the master. Read! You’ll absorb it.” And Chekhov on writing: “Write as much as you can! Write, write, write till your fingers break.”

John Dufresne is the author of seven novels, including I Don’t Like Where This is Going and No Regrets, Coyote. Among other honors, he has received a Guggenheim Fellowship and is a professor in the MFA program at Florida International University. He lives in Dania Beach, Florida. For more information, please visit www.johndufresne.com.

John will be joining our Pitchapalooza panel in Miami on May 7, 2016, at 2 p.m. Learn more at the Miami Herald.

JOIN OUR NEWSLETTER TO RECEIVE MORE INTERVIEWS AND TIPS ON HOW TO GET PUBLISHED.

We’ve been to the South Dakota Festival of Books twice so far, and we have now discovered two amazing writers who came to the festival without a book deal. Both now have books about to come out. Our conclusion is that there are lots of great writers in South Dakota, and many of them go to that festival. As soon as we met Jerry Nelson, we knew he was the real deal. He has that subtle, dry Midwestern wit that sneaks up behind you and then whacks you right in the funny bone. Since he’s writing about experiences that are so far out of the norm from people on either coast, we knew he’d need a special kind of publisher. We’ve seen over and over again how New York publishing doesn’t quite get this kind of Midwestern book and doesn’t understand what a big audience it has. Jerry’s opus, Dear County Agent Guy, is finally ready for publication, and we are so happy to see this book spread its wings and fly out into the world. We thought we’d check in with him to see exactly how he did it.

To read the full interview on the Huffington Post, click here.

The Book Doctors: When did you first become interested in being a writer, and how did you learn to be one?

Jerry Nelson: I was in junior high school when I read a newspaper column by humorist Art Buchwald. My first reaction was “Newspapers don’t print stuff like this! Newspapers are supposed to be serious and stodgy!” My second reaction was “Where can I find more of this?”

When I was a kid, I never imagined myself becoming a writer. My only goal in life was to be a farmer like my dad and his father before him. I didn’t think that a formal education was necessary for achieving this goal. I put in the minimum amount of effort required of me at school and barely graduated from high school.

I learned to be a writer by reading, which I call “feeding the machine.” Reading enables you to travel to exotic lands and experience new sights and sounds.

The next step toward becoming a writer is to do some actual writing. There are many who say, “I should really write a book!” yet never get past the “should” part. We all have that little voice in our head who is constantly narrating the passing scene. Writing is simply committing that narrator’s words to paper. In essence, I learned by doing.

BD: What are some of your favorite books and why?

JN: I thoroughly enjoy everything that Dave Barry has ever written. He is one of those writers who has the uncanny ability to make the reader spontaneously snort with laughter.

I adore the outdoor writer Patrick F. McManus. When our sons were young, it became a tradition to read one of Pat’s humorous essays to them as a bedtime story. This resulted in much giggling from the boys and from me.

At my bedside is Volume I of The Autobiography of Mark Twain. I dip in and out of it randomly, which I understand is pretty much the method Twain used to write it. Time spent with such a virtuoso is never wasted.

I also loved The Grapes of Wrath and The Great Gatsby. The list goes on and on.

BD: Read any good books lately?

JN: Our son and daughter-in-law recently gave me a signed copy of Failure is Not An Option by Gene Kranz. It details the author’s experiences as a NASA Flight Director in the early days of our nation’s space program and during the near-disaster that was Apollo 13. These things took place when I was a kid, so it’s like time traveling for me.

I just finished Leaving Home, a collection of The News From Lake Wobegon essays by Garrison Keillor. They are from the early days of A Prairie Home Companion, so most of them seemed new to me. Reading them was nearly as pleasurable as hearing them. They gave me a chuckle and filled me with a deep sense of home.

BD: You have been compared to Mark Twain and Garrison Keillor. How do you feel about that?

JN: It totally blows my mind!

As a boy, I first fell in love with Twain when I read Tom Sawyer. I then proceeded to devour Huckleberry Finn and almost everything Twain has written. He was an American original and is still the undisputed master of his genre.

I first heard Keillor’s voice one Saturday in the mid-1990s when I was feeding my Holsteins. A commercial for Bertha’s Kitty Boutique came through the speakers on my tractor’s radio and I was instantly hooked. I cannot imagine a Saturday evening without A Prairie Home Companion.

Keillor is a living legend and being compared to him is an unspeakably huge honor. Keillor grew up in Anoka, Minnesota, which is four hours from our farm, so it’s natural that our styles might have a similar terroir. The difference is that Keillor writes about Norwegian bachelor farmers, while I once was a Norwegian bachelor farmer.

BD: Tell us about how your professional writing career started.

JN: In 1996, my area was suffering through an extended period of wet weather. It had been so wet for so long that cattails were beginning to grow in my field where there should have been rows of corn.

Feeling frustrated and helpless, I penned a spoof letter to Mel Kloster, my local county extension agent. In the letter, I asked Mel if he knew of a cheap, effective herbicide that could control the cattails. And while he was at it, maybe he could advise me on how to get rid of all the ducks and powerboats that were out in my corn field.

Instead of using a normal salutation, I started the letter with “Dear county agent guy.”

Mel told me that he had enjoyed my missive and that I should get it published somewhere. I replied that I had zero training as a writer and didn’t know the first thing about publishing.

Despite my reservations, I took Mel’s advice and showed the letter to Chris Schumacher, editor of our local weekly newspaper, the Volga Tribune. Chris read the letter and said, “Yeah, I’ll publish this. Do you have any more ideas?” I replied that I had maybe one or two. “Keep them coming,” he said, adding, “What should we call this?”

I asked Chris what he meant by “this.”

“It’s a newspaper column,” said Chris. “How about using the salutation, ‘Dear county agent guy?'”

I replied that this was fine by me and that’s all the thought that went into it. I have written a column each week ever since.

That tiny spark was the beginning of my writing career. As my confidence in my abilities grew, I began to get some of my work published in the nation’s premier farm magazines. I also began to submit scripts that were used on A Prairie Home Companion. I don’t recall exactly how much I was paid for those scripts, but do know that the money was put toward our home heating bill.

BD: You been doing your column “Dear County Agent Guy” for a long time, what have you learned about America by writing about this very particular part of it?

JN: I have learned that folks who live in the Midwest feel that we are all part of a large, extended family. I often write about what’s going on in my life, so my wife and our two sons have provided me a lot of fodder over the years. I have had numerous people say to me, “I feel like I know your family better than I know my own!”

A high school girl recently told me of a family ritual that involves my newspaper column. My column arrives at their home on Friday. When they sit down for their meal that evening, one of the family members reads my column aloud at the table. What I have written then becomes the official topic of discussion during the meal.

Reactions such as those are very gratifying and extremely humbling. They also drive home what a huge responsibility I have to my readers.

BD: What are some of your favorite stories in the collection?

JN: That’s like asking which of your offspring is your favorite child! I cherish them all equally.

But if you held a gun to my head, I might say that “Electric Fencing 101” has a special place in my heart, mainly because it’s mostly true with only a little embellishment here and there. That piece illustrates what it’s like to raise kids on the farm.

Another piece that is special to me is “The Four Seasons of Farming.” It’s one of the more ruminative articles in the book, an essay that speaks to my deep connection with my family, the land and the rhythms of the earth.

BD: Your family have been dairy farmers for four generations. How has farming changed since your great-great-great-grandparents were milking cows?

JN: When my ancestors homesteaded in Dakota Territory, they milked cows the same way it had been done for 10,000 years, that is, by squatting beside a cow and squirting the milk into an open bucket.

Modern dairy farmers utilize 21st century technology. Some dairies have milking parlors that can milk dozens of cows at a time. Over the past few years, robotic milkers have come to the fore. These machines can clean the cow’s udder, attach the milking unit and apply a post-milking teat dip, all without any direct human supervision. Daily milk production and numerous other data points can be accessed via your PC or your smart phone. The robot will send a text to your cell phone if it needs help with an issue.

Cow comfort is paramount on the modern dairy. It used to be that the cows were cold in the wintertime and suffered through the heat during the summer. Nowadays, dairy barns are climate controlled and some dairy farmers have even opted to equip their stalls with water mattresses. Many dairy operators put electronic necklaces on their cows that will track such things as how many steps the cow takes each day and how much time she spends chewing her cud.

My wife wants to put a similar necklace on me so that she can quantify how much time I spend doing actual work and how much time I waste goofing off. I am adamantly opposed to this idea.

BD: Many of our readers want to know, how exactly do you train a husband?

JN: My wife says that one of the things that first attracted her to me was the fact that I have five sisters and was thus “pre-trained.”

From what little information I have managed to gather, husband training is more of an art than a science. It’s also an ongoing, never-ending endeavor. I have heard wives say that it can take up to 50 years to get a husband properly trained.

Husbands are actually fairly simple creatures. We respond positively to rewards and have a deep aversion for unpleasant experiences. If you discover a training method that works well for your Golden Retriever, odds are it will also work for your husband.

BD: We hate to ask you this, but what advice do you have for writers?

JN: There are six simple rules to becoming a better writer: read, read, read, and write, write, write.

Read everything you can lay your hands on. Read the greats and the not-so-greats, anything that will stretch your imagination and your vocabulary. Make certain that you consume a healthy dose of poetry on a regular basis.

As a writer, don’t be afraid to put yourself out there. Recognize that you are not perfect and will never be able to please everyone. Such is life.

It has been said, “Be bold and mighty forces will rush to your aid.” I have found this to be true throughout my years of beginning each week with the words “Dear county agent guy.”

Jerry Nelson and his wife, Julie, live in Volga, South Dakota, on the farm that Jerry’s great-grandfather homesteaded in the 1880s. In addition to his weekly column, his writing has also appeared in the nation’s top agricultural magazines, including Successful Farming, Farm Journal, Progressive Farmer, and Living the Country Life. Dear County Agent Guy is his first book.

Arielle Eckstut and David Henry Sterry are co-founders of The Book Doctors, a company that has helped countless authors get their books published. They are co-authors of The Essential Guide to Getting Your Book Published: How To Write It, Sell It, and Market It… Successfully (Workman, 2015). They are also book editors, and between them they have authored 25 books, and appeared on National Public Radio, the London Times, and the front cover of the Sunday New York Times Book Review.