I’m lucky enough to say I’ve now known Jerry Stahl for over a decade, and we’re both still alive. Ten years ago you could’ve gotten very good odds betting against that happening. Now we’re both OG Dads: Old Guy Dads. So it was with great joy that I found out he had compiled a book out of the filthy and sweet, perverted and lovely, hysterical and horrifying columns he wrote for Rumpus about becoming a father in what should be the beginning of his Golden Years. I had to find out why he was willing to strap on the diapering hat while in a position to be adult-diapered himself. By the way, if you’ve ever been a parent, or ever been a kid, and you’re not squeamish (hell, even if you are squeamish, especially if you’re squeamish!) you need to read this book.

To read Jerry’s interview on the Huffington Post, click here.

David Henry Sterry: First of all, what were you thinking becoming a dad when you are well over the age when that sort of thing even remotely makes sense?

Jerry Stahl: It didn’t make much sense the first time around either—when I was strung out like a lab rat. Maybe the little fuckers just need to show up. If people waited for the right time, the world might be underpopulated, instead of over. But regardless of logic or circumstance, you love them, and you get to love them, in a way that you can’t or don’t or never will love anyone or anything else. Not sure making sense is part of the package.

DHS: Do you feel it’s easier to be a good parent when you’re taking heroin on a regular basis, or when you’re not?

JS: No getting around it, it’s easier to be up all night and you stay pretty even-keeled on smack. I was never a nodder—I could function on it—the problem was functioning without it. (Like Burroughs said, when asked about why he did dope, “So I can get up in the morning and shave.”) That said, it’s impossible to be kicking heroin—when you are in the ultimate needy baby-state—and also taking care of a baby. (There are no bigger babies than junkies.) The two needinesses can’t co-exist. I wouldn’t advocate for heroin-fueled parenting.

DHS: I love that you invoke Yates at the beginning of the book about the “terrible beauty” of raising a girl. I myself have a seven-year-old, and every day I face the terror, and the beauty. Can you give us an example of those two things in your daily life?

JS: The examples are pretty much non-stop. I’m as blown away by seeing my 26-year-old navigate the world as seeing my rambunctious 3-year-old discover it. The terrible part is knowing what happens to beauty, and to all good things in this world. Nobody gets out alive, as has been said more originally and more intelligently before. Somehow you don’t—or I didn’t, any at any rate—feel it as profoundly until having children.

Today my little one cracked her head open at pre-school. It’s her third visit to the ER. The fragility of the whole enterprise—that, too, is terrible and beautiful. The unlikeliness that anything survives. And in our current epoch, and the even worse Naomi-Klein dystopia of parched earth, poisoned food, nuclear moronicism (and these are just the good things) that awaits, the terror is even more profound. The guiltiest thought of all is that older guys—older people—may be the lucky ones. Because what’s going to happen after we’re gone—that may be the worst terror of all.

DHS: I know that as a former addict, lunatic and indulger in high-risk behavior, I am worried that my crazy shit is going to be inherited by the sweet, innocent little child I have spawned. Do you?

JS: I don’t worry about it. Who knows what’s nature and what’s nurture? My whole theory of childrearing is “try and fuck them up the opposite of the way you were fucked up.” With any luck, knowing there’s that propensity for crazy, high-risk shit, you can try not to feed the beast. But if the beast is coming, the beast is coming.

DHS: This seems so much like a new Netflix show; have there been thoughts and inquiries about transitioning this from a book into a TV series?

JS: Always thoughts, always inquiries. You never know. Johnny Depp, God bless him, optioned my novel, I, Fatty, over a decade ago, and it’s still on the soon-to-be-never-made shelf. So I take it all with a big screen-sized grain of sea salt.

DHS: For me, one of the most challenging things about being a fifty-something with a young child is having to hang out with all the other parents. Do you have any techniques you like to share for dealing with the helicopter/over-entitling/attachment-disordering parents?

JS: I actually can’t. Beyond lighten the fuck up. I am not the helicopter guy. Maybe it’s because I have a an older child who’s 26 and one of the funniest, coolest, smartest, most beautiful, big-hearted and together people I know on the planet—despite having had me as a father. That is a long-winded way of saying, whatever one’s intentions, kids are such nuance-sponges that intentions don’t matter.

If I’m uptight she’s gonna sense it and it’s gonna make her uptight. I know what it’s like to be thus psycho-emotionally infected. Let’s just say my own parents were not on the cover of How To Parent And Not Raise A Neurotic Freak magazine. So, if nothing else, I know what not to do—and how not to be. Helicoptering and the rest of it is not the problem; the human condition, that can be a bitch.

DHS: Does it bother you when people ask if you are the grandfather? I thought it would, but it really doesn’t bother me at all.

JS: I haven’t got the gramps thing yet. I looked older at 39 than 59, thanks to the twin fangs of virulent Hep C and a monstro dope habit. (Or—who am I kidding—if not older, at least greener and moldier.) Maybe because LA is so morally bankrupt there are plenty of old fucks running around in my situation. Not that it implies moral bankruptcy. But it’s not exactly an aberration. DeNiro just had a kid, and he’s got a decade on me. The goalpost is forever moving.

DHS: Do you worry about when your child gets old enough to Google you and asks, “Dad, how come you used to like heroin so much?”

JS: That’s funny. I told my older daughter she could read Permanent Midnight when she’s 40. So far she’s had no trouble holding off. In the meantime, I don’t think kids, or even twenty-somethings, are overly concerned with their parents’ history. They’re too busy trying to make their own. At least I don’t have any secrets about the past. For better or worse, they’re all out there to read or watch on the Sundance Channel at four in the morning when they rerun the movie.

DHS: I hate to get all “happy happy glory hallelujah” on you, but when I look back on my life, I realize I should be dead a dozen times over by now, and I have a profound sense of gratitude that I somehow didn’t die young, especially when I look at my child doing something beautiful and spectacular. Does this happen to you, or am I just crazy?

JS: Maybe both. Much of my life was spent trying to endure life—as opposed to live it. But somehow, knowing what I do is for someone else, some tiny, beautiful weirdo who thinks rabbits live under the bed making fun-candy, I can rise above, can feel all the joy I could never feel when it was just me. Even if I don’t feel particularly joyful—I still have the temperament of a guilty survivor—I can still make it about her enough so it doesn’t matter what I feel. Nothing makes you forget yourself like a child.

And yeah, it’s fucking crazy. But it’s the best kind of crazy there is. We know the odds against all of it: being alive, having a child, having a healthy child … all of it. But here the fuck we are.

DHS: As the Book Doctors, Arielle and I are always looking for new and interesting ways for people to get published. What was the process of taking your column and turning it into a book?

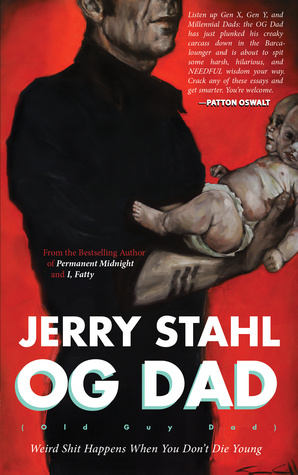

JS: Pretty simple actually. I gathered up the stuff I had and wrote a bunch of new ones so people who actually read the columns on The Rumpus would want to grab a copy too. Then I asked a painter friend of mine, Shannon Crawford, who also did the cover an earlier book, Bad Sex On Speed, to come up with something for the cover: me holding a tiny, two-headed baby, who happens to have my own little girl’s face. Things rarely go that smoothly, but once in a while they do.

DHS: Do you have any tips about writing about your own life? Do you have any tips for Old Guy Dads?

JS: My only advice: don’t listen to me.

Beyond that, I don’t give advice. My experience, however, is if writing about your life (or writing in general) is a choice, you probably don’t need to be doing it. If, however, you’re doing this… thing—and are compelled to keep doing it—then you probably wouldn’t listen to anybody anyway. From the time I was 16 on, I had people telling me not to write, to get a day job, etc… etc… If I could have, I would have. But I have no particularly marketable skills, so of course I became a writer. I admire people who can come up with gimmicky ideas and make a shit-ton of money. I just don’t find them particularly interesting. At the end of the proverbial day, I’m always gonna take Raskolnikov over Romney.

As for Old Guy Dads—well, speaking for myself, I used to think we were only here for a cup of coffee, but that’s no longer true. Old guys, we’ve had the coffee, and we’re waiting for the check. Might as well enjoy yourself—and, more importantly, try to help other people do the same—before it’s time to settle up. And always tip big.

Author, journalist, and screenwriter Jerry Stahl has written eight books, including the memoir Permanent Midnight (made into a film with Ben Stiller and Owen Wilson), and the novels Pain Killers and I, Fatty (optioned by Johnny Depp). Former Culture Columnist for Details, Stahl’s widely anthologized fiction and journalism have appeared in a variety of places, including Esquire, The New York Times, Playboy, The Rumpus, and The Believer. Stahl edited the anthology, The Heroin Chronicles, published by Akashic Books; and his latest novel, Bad Sex On Speed was released by A Barnacle Book, an imprint of Rare Bird Books. Stahl co-wrote the HBO film Hemingway & Gellhorn with Clive Owen and Nicole Kidman. His latest novel, Happy Mutant Baby Pills, was published by HarperCollins.