If you don’t know how to write a great query letter, you’re going to have a very hard time getting your writing published by anyone except yourself. The Book Doctors, was a little fun flair and savoie fair, break it down with simple easy-to-understand instructions. Start #amquery-ing right! Get published now!

Tag: novel

To read on-line click here.

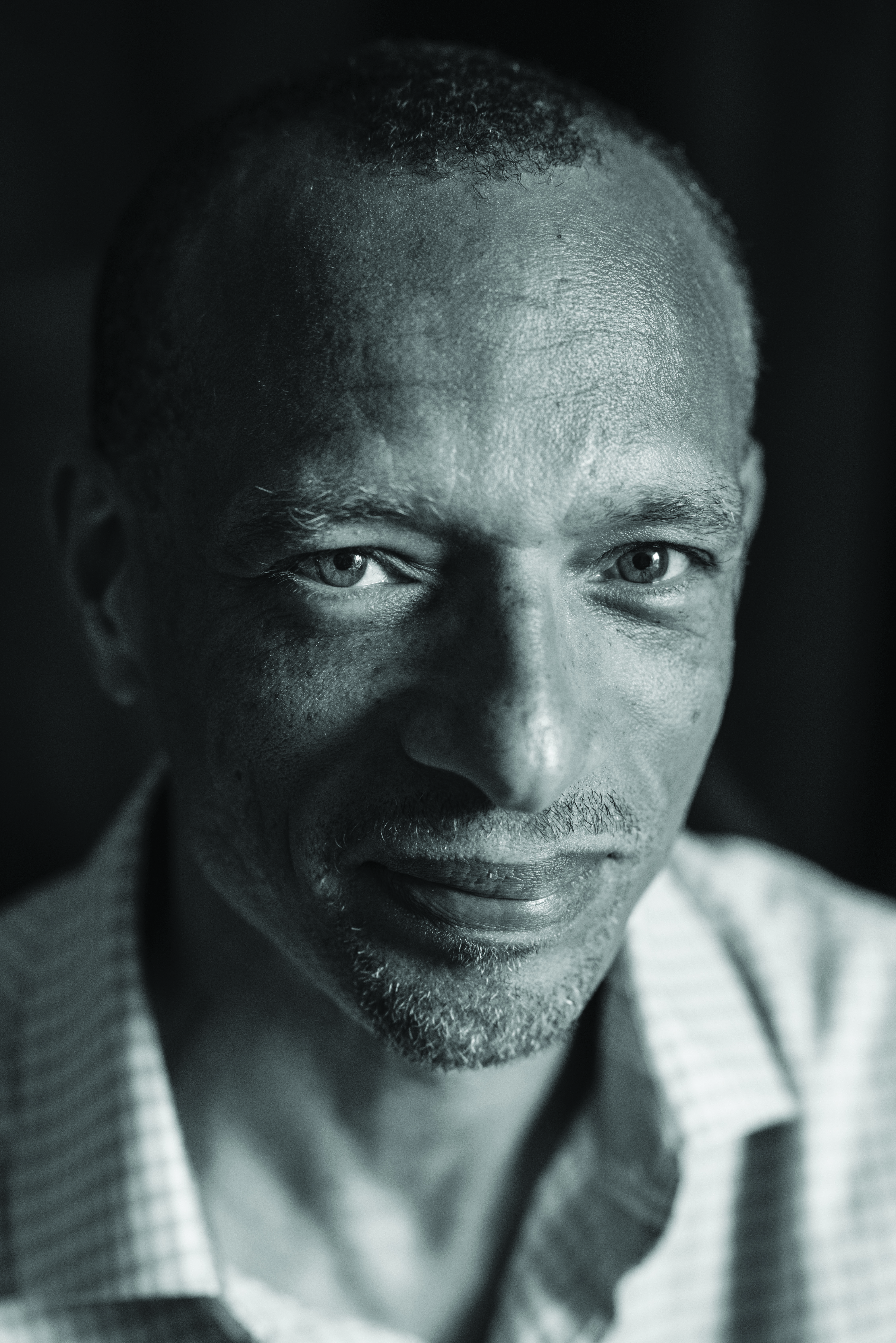

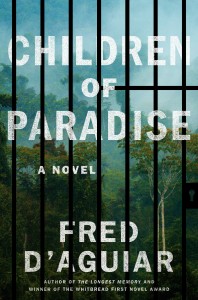

I’ve long been fascinated by the events surrounding the Jonestown tragedy. I’m particularly interested, as a parent, in what would lead someone to poison their own child. It seems unthinkable. And yet we all know it happened. So I was drawn to Children of Paradise, and I found the treatment of this very disturbing and real-life tragedy beautiful and compelling. The New York Times said, “D’Aguiar depicts the plight of Trina and the other children with heartbreaking immediacy.” So I sat down with its author, Fred D’Aguiar to talk about Jonestown, kids and how he wrote this wonderful book.

DAVID HENRY STERRY: What was your inspiration for writing a book about the Jonestown tragedy?

FRED D’AGUIAR: Jonestown happened in Guyana. My parents are Guyanese and I grew up there. I was in London when I heard about the murder suicides. In 1998, twenty years after the event, I wrote a long poem in an effort to understand why so many Americans ended up in such an idyllic landscape — the Amazonian basin interior of Guyana — only to die en masse. I made a radio program for the BBC about Jonestown in 2003 and it occurred to me that the psychology of faith had to be explored by me in a sustained work driven by character narrative rather than the lyric of the poem. I’ve been writing (and rewriting) the novel since then until now with breaks for poetry and plays, teaching and life. But don’t ask me about my failed novels — writers hate to air dirty laundry (this writer does).

DHS: You write from the perspective of a gorilla with shocking verisimilitude, how did you research the inner mental and emotional landscape of Adam the gorilla?

FDA: I’ve always believed that the danger of a reflex tendency for anthropomorphizing nature (of always seeing things in terms of our own primate and primary conceits) brings with it an over-assumption of empathy when all that is gained is a domestication of the unknown in terms of our limited, superior colonization instincts. We have an encounter but learn nothing from it. And not only a colonization of nature’s prowess in terms of our limited human understanding of it but a gesture of intuitive admission that nature has a language that we need to learn in order to really function in harmony with the planet. Right now our civilization is built on using up the earth and finding some other location for the future of the species (a stupid gamble, look at Las Vegas; think of Shelley’s poem <em>Ozymandias</em>). I’ve maintained my interest in nature writing from my first encounter with the works of Desmond Morris during my teens to the euphoric and vatic veneration of nature by Barry Lopez.

I wanted Adam (what’s in a name?!) to be the outside figure, in the commune locked in a cage but outside the commune’s reasons for being together, and in league with his Edenic surroundings as he witnesses a slice of humanity spiraling towards self-destruction. I’ve been to Jonestown and seen a bit of the landscape in the Amazonian region. The jungle with its rock escarpments, rivers, trees and waterfalls and flora and fauna, is a cathedral in its grandiosity (here I am anthropomorphizing but in keeping with the Romantics), it is a place of worship, a spiritual reliquary (if only we paid attention to it).

DHS: For that matter, how did you get into the mindset of a kid who was at Jonestown during one of the most unspeakable tragedies of the 20th century? And the POV of Preacher, who seems very much to be Jim Jones in this scenario?

FDA: I trained and worked as a psychiatric nurse way back in my early 20s and the work experience has remained with me ever since in the focus of my writing on the psychological and psychical aspects of a character’s experience. There are writers who have helped me to frame this in my fiction. First, Wilson Harris (b.1921). His fiction reacts to the landscape as if it were a structural determinant of his prose. Meaning, when you read him you feel as if the jungle’s architecture dictated his sentence structures. Harris is Guyanese and worked as a surveyor in Guyana’s interior and he wrote a 1996 novel titled <em>Jonestown</em>, which connects the tragedies in the jungle to a tradition of dying and sacrifice going back to antiquity, to Olmec Mayan times. Second, Derek Walcott. He handles imagery with metaphoric zeal. He ties the blood rhythms of thought to a sensuous instruction gleaned from our world. Three other seminal texts have been Alejo Carpentier’s <em>The Lost Steps</em> and Juan Rulfo’s <em>Pedro Marano</em> and Jean Rhys’s <em>Wide Sargasso Sea</em>.

DHS: You gave your novel the same name as a very famous film about the German occupation of France, why was that?

FDA: That happens to be my second most favorite film ever! The definite article in the title of the film means a lot. The sly mechanisms for defying despotism while it surrounds you, all rooted in art has to be instructive or my whole grain bread and peanut butter breakfast consumed this morning for its goodness is a cruel hoax. I wanted to connect with a former period of despotism in history and prompt the reader to think about children in history and how childhood is constructed and destroyed in turn and made anew by the experience of the arts.

Don’t laugh, but my first most favorite film ever happens to be one I got into in my early teens — <em>Roots</em>, the TV series. Yes! Don’t ask me why! Ask me why! Well, Alex Haley’s <em>Roots</em> (include the book as well) made me aware of the importance of knowing about black history and the necessity of art for a vital and examined life, and storytelling, character, landscape, emotion, intuition and persuasion as ethical frames for understanding (though puzzlement endures) and improving (though the work is never done) the world (and what a beauty it is) in a short life (and how prized).

DHS: Why do you think, in the end, people were willing to kill themselves and their children when their messianic leader told them to?

FDA: By the time the moment of murder-suicide arrived the people in the commune had experienced a prolonged period of indoctrination and torture (sleep deprivation, starvation and humiliation through public beatings and public shamings). They were at the end of their tether, nerves strung out, exhausted and ripe for manipulation. Add to that their isolation in Guyana’s jungle interior from the scrutiny of the outside world and the communards entirely subjected to the maniacal will of Jones. What was left of their will had been systematically eroded by Jones’ technique (think of Erving Goffman’s Total Institution) of repression to a point of hypnotic obedience (though it must be said that there was resistance by some to the bitter end as proved by the group that escaped by running into the jungle). They were told to drink or be shot, some choice.

DHS: Do you outline your plot before you start writing?

FDA: No. I began this lucky artsy-fartsy life that I now lead way back in my youth when I was a hungry and angry poet (hungry for meaning, angry for justice). As a result, I continue to write from a feel (mostly of terror) and a string of images (that play havoc with my nerves). The feeling is deeply linked to the imagery. Next, I find the people in the picture who might best exemplify that mood and exude the things that I am feeling. In the case of this novel the plight of the children attacked my nerves and left me wanting to replay their probable instances of childhood before their inevitable and painful deaths.

DHS: You are also a poet and playwright. How did poetry and writing for the stage affect writing <em>Children of Paradise</em>?

FDA: Poetry is the art of compression, of distillation; fiction appears to expand like an accordion pulled open limitlessly for a beautiful sequence of sound and meanings. Plays speak through characters on a stage in a suspension of real time for a dramatic carve-up of time as feeling and instruction. I crave instances of articulation in all mediums depending on my mood. I blame my multi-genre body on my experience of three landscapes, my birth and long residence in the UK, my childhood spent in Guyana and the adult realities of settling for life in the US.

DHS: You were teaching at Virginia Tech when a student went on a shooting rampage. What was that like, and how did this lead to you writing about Jonestown?

FDA: April 2007 was a nightmare for me. (I’ll count is as such until I die.) I lost a student who was in my Caribbean class. She was shot dead while in her French class. I happened to be on campus that morning. I have always loathed guns due to my residency in the UK where guns are blessedly rare. But after 2007 I am now so very much desirous of a ban on the possession of all firearms by private citizens — they belong to a primitive remnant of our warlike bodies. And we have a standing army anyway. I worry about the ready availability of personal firearms and the lack of respect for mental illness. It is a serious affliction in need of structural investment by this remarkable country. But what do I know? I think the education budget should be swapped with the defense budget.

DHS: Why do you think “drinking the Kool-Aid” has become part of our everyday vernacular?

FDA: It is a cruel misnomer extrapolated from Jonestown and one of the reasons why I wrote my novel to depict resistance rather than blind obedience to messianic sadism. We apply the term to denote a total surrender to an idea or force. In Jonestown there was resistance to Jones and that is why he needed a remote location and a regime of mental and physical torture that resulted in an erosion of the will of his followers. It seems as if the media has succeeded in its cookie-cutter way of leaving the popular memory with an unimaginative phrase to represent a tragedy. I took pains in my novel to chart the stages of this breakdown of the will of the community and I showed pockets of resistance to Jones as well. The cool aid was just the final act in a play of death, along with bullets, beatings, sleep deprivation, starvation and marathon sessions of Jones’s preaching that was recorded and relayed on speakers around the compound, all hours of the day and night. I wish it amounted to more than yet another example from recent history of a failed ecumenical tool.

DHS: After living with this story for so long, what are your final takeaways?

FDA: I quote as an epigraph, 1 Corinthians 13:13 and I stick with that. If I say it, people will hear the Beatles tune, “all you need is love” pah dap-pah, pah bah-dah, because it is so obvious that it precludes speech. But I’ll say it anyway for the record. Love (with cooperation) is a stronger (and preferable) force to hate (and competition). The evidence for the latter is technological advancement at a price of a dying planet… some advancement when we’ve mortally wounded the host of all species.

DHS: What advise do you have for writers?

FDA: First, Oscar Wilde’s adage that, ‘advice is an excellent thing not to follow but to disregard.’ Second, that they should read, read, read and get involved in something other than writing, and write, write, write. The arts of the imagination help us to understand the present and the past, and live coterminously with the planet and everything on it. Doing so should affect in positive ways what the future will be; not doing so merely accelerates our terminal decline. The literate imagination may well be our most powerful asset of our naturally inquisitive bodies and it is free. Go for it!

Fred D’Aguiar is an acclaimed novelist, playwright, and poet. He has been short-listed for the T.S. Eliot Prize in poetry for Bill of Rights, a narrative poem about the Jonestown massacre, and won the Whitbread First Novel Award for The Longest Memory. Born in London, he was raised in Guyana until the age of twelve, when he returned to the UK. He teaches at Virginia Tech. Children of Paradise is his newest novel.

David Henry Sterry is the author of 16 books, including <em>Hos, Hookers, Call Girls and Rent Boys: Professionals Writing on Life, Love, Money and Sex</em>, which appeared on the front cover of the Sunday New York Times Book Review. His new book Chicken Self:-Portrait of a Man for Rent, 10 Year Anniversary Edition</em></a>, has been translated into 10 languages. He is a finalist for the Henry Miller Award.

To you the interview on Slashed Reads, click here.

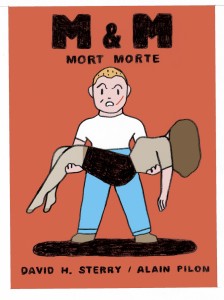

David Henry Sterry is the author of Mort Morte, an absurd, hilarious, tragic and disturbingly haunting comedy published by Vagabondage Press in January 2013. David is the author of 16 books and a finalist for the Henry Miller Award.

David Henry Sterry is the author of Mort Morte, an absurd, hilarious, tragic and disturbingly haunting comedy published by Vagabondage Press in January 2013. David is the author of 16 books and a finalist for the Henry Miller Award.

What is your book about?

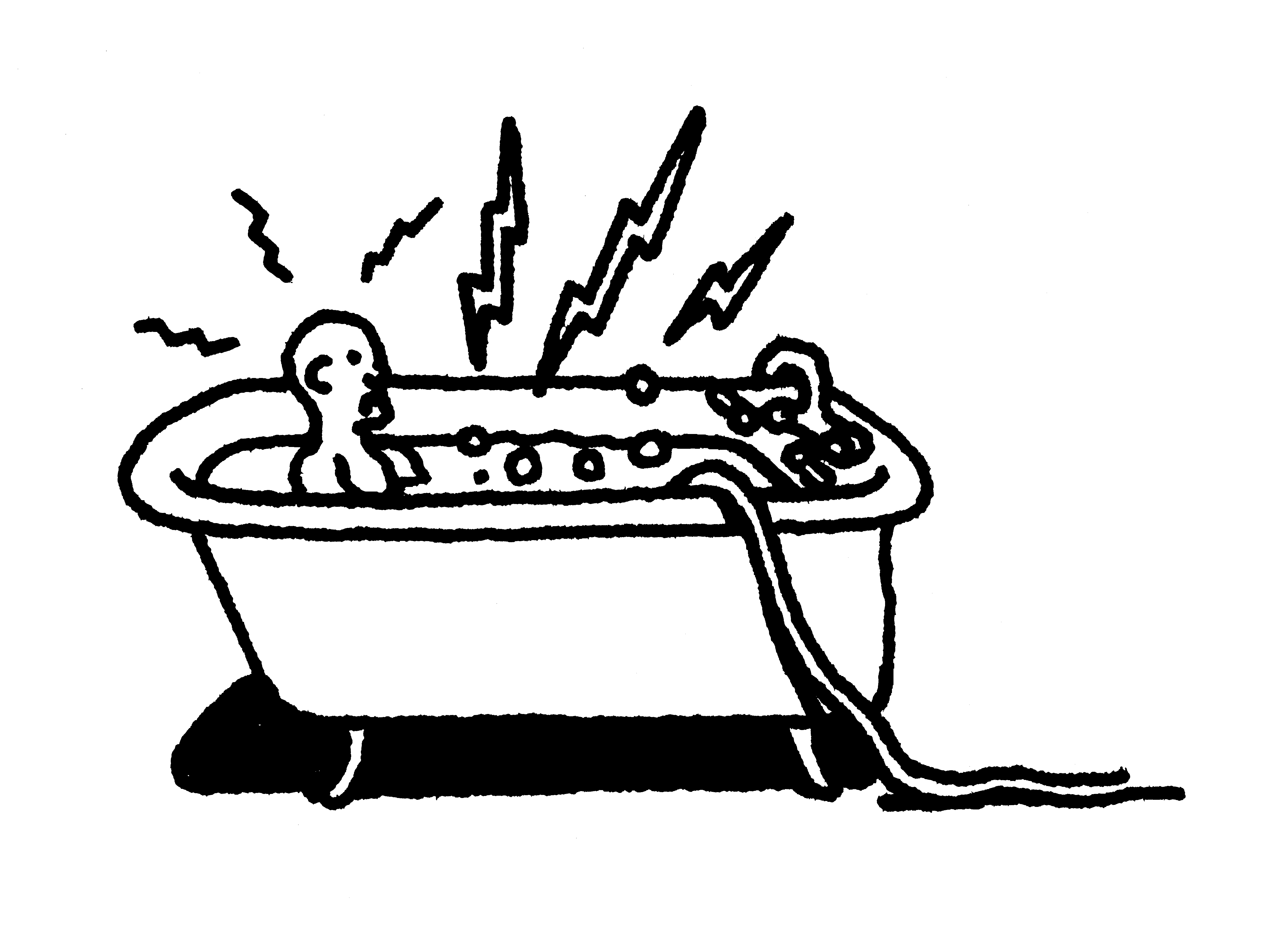

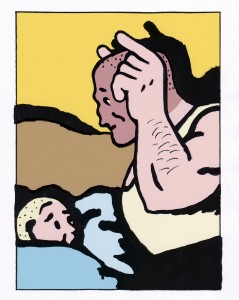

On my third birthday, my father, in an attempt to get me to stop sucking my thumb, gave me a gun. “Today son, you are a man,” he said, snatching the little blue binky from my little pink hand. So I shot him.

So begins my novel Mort Morte. It’s a macabre coming-of-age story full of butchered butchers, badly used Boy Scouts, blown-up Englishman, virginity-plucking cheerleaders, and many nice cups of tea. Poignantly poetic, hypnotically hysterical, sweetly surreal, and chock full of the blackest comedy, Mort Morte is like Lewis Carroll having brunch with the kid from The Tin Drum and Oedipus, just before he plucks his eyes out. In the end though, Mort Morte is a story about a boy who really loves his mother.

Is the book based on events in your own life?

Strangely enough, Mort Morte was my attempt to tell my life story. Fortunately, I didn’t kill my father on my third birthday. But my real life story is even more sick and deranged. Eventually I did tell my agent about my real life story and she urged me to write a memoir. This became Chicken: Self-Portrait of a Young Man for Rent. The 10 Year anniversary edition of that book has just been released. As a result Mort Morte got put on the back burner. For 20 years. That’s why I was so excited when Vagabondage agreed to publish the book. 20 years is a long time to go between writing a book and getting it published.

What twists did the book take that surprised you?

The first twist came when I wrote the first sentence. Honestly, as I said, I was trying to tell my life story, and the first sentence just came out fully formed. I have no idea how or why. Clearly I must have some sort of repressed desire to shoot my father. Fortunately I have been able to repress that desire. For now anyway. Actually, the whole book was a series of twists. I didn’t plan it out or outline it or plot it in any way shape or form. It just came flowing out of me. The first draft took me three weeks to write. Mind you it took me over a year to revise and edit the book.

But it was almost like being in a fever dream. It just kept pouring out. All I had to do was get out of the way.

Are you a people watcher? If so, are they in your stories?

Absolutely. I learned most of the things I know about humans by watching them. I was a professional actor for 15 years before I wrote my first book, and I spent a lot of that time learning how people walked, talked, what they were saying with the language of their body, what was being communicated between the lines.

I moved around a lot when I was a kid, I never went to the same school for two years in a row until I was in college. So I was always the new kid, the outsider, the person who didn’t have friends. So I watched. I observed. I learned how to act like everybody else. And whenever we moved, I learned how to imitate the local accent. It was great training as an actor. It was also great training as a writer, to get the rhythms of the way people really speak.

One of my pet peeves is when you can actually hear the writer writing as a character in one of their books is talking. Almost all the people in my books are human beings I have observed. When I’m writing a memoir of course I try to remember exactly what they said, exactly what they looked like and exactly how they acted. When I’m writing a piece of fiction I take what’s there and let my imagination run wild. Either way, it starts with the way people really look and talk and act.

Do you consider yourself an introvert or extrovert?

Yes. I am a Gemini. But I don’t really believe in all that astrological crap. Even though that’s exactly what a Gemini would say. But as a Gemini I have two very distinct parts of my personality. I’m a hermit and I love holing up in my man cave and escaping into my imagination. Woody Allen once said the only things in life you can really control are art and masturbation. I try to keep my fingers in both those pies every day, in the privacy of my subterranean lair. But I’m also kind of an exhibitionist, and I love to go out and do book events and go on tour and present at writers conferences and book fares. So I kill both birds with just the one stone.

What are our thoughts on writing as a career?

In addition to being the author of 16 books I’m also a book doctor. I help talented amateurs become professionally published authors. So I’ve consulted with literally thousands of writers.

And I tell them all that by far the most important thing you can do if you want to have a career as a writer is to figure out how to make money.

It’s very hard to make money as a writer. I’ve been lucky in that way. But I’m also a hustler. That’s one of the things I learned in the sex business. How to hustle. Lots of writers don’t know how hustle. Let me be clear, I don’t mean hustle as a way of scamming, grifting, or ripping someone off. I mean hustle in the sense that you get someone to do what you want them to do.

I want publishers to give me money for my books. So I identify which publishers I want to work with who are most compatible with what I do, then I research them to the point of stalking. And of course I want readers to buy my books and fall in love with them. So I identify individuals and groups who I think will love what I’m doing and be passionate about my books.

As is the case with all hustles, you actually have to have Game. You have to make a good product if you want someone to buy it over and over again. If you try to pull the wool over someone’s eyes, eventually they will stop buying what you’re selling, and in the worst case scenario they will come at you with a lead pipe and try to split your skull open.

The great maxim of businesses as far as I’m concerned is: “Find out what people want, and give it to them.”

Mind you, I have books that I write for love, and books that I write for money. Mort Morte was more of a love book. That being said, I have made money off it.

What is your advice for other writers?

Research. Network. Persevere. And oh yeah, write. Write, write, write, write, write, write, write, write, write, write, write, write, write, write, write, write, write, write, write, write, write, write, write, write, write, write, write, write, write.

What inspired you to write your first book?

I was a drug addict and a sex addict and I knew I was going to die unless I changed who I was and what I was doing. After a long search I finally found a hypnotherapist. She helped me get my addictions under control. I was a professional screenwriter in Hollywood at the time.

My hypnotherapist suggested I write about my life, since it was so much more interesting than the stupid ridiculous screenplays I was selling to Hollywood. I took her advice.

I found I really enjoyed it. And it was absolutely essential in staring down and overcoming the demon monkeys inside me which were destroying my life.

What do you want to say to your readers?

Buy my books. Tell your friends to buy my books.

How do you prepare to write love scenes?

Fall in love. Have lots of great sex. Have lots of bad sex. Get dumped. Rinse. Repeat.

Author Profile

David Henry Sterry is the author of 16 books, a performer, muckraker, educator, activist, and book doctor.

His new books are Mort Morte, and The Hobbyist (Vagabondage, 2013).

His memoir,Chicken Self:-Portrait of a Man for Rent, 10 Year Anniversary Edition has been translated into 10 languages.

He’s also written Hos, Hookers, Call Girls and Rent Boys: Professionals Writing on Life, Love, Money and Sex, which appeared on the front cover of the Sunday New York Times Book Review.

He is a finalist for the Henry Miller Award.

He has appeared on, acted with, written for, been employed as, worked and/or presented at: Will Smith, a marriage counselor, Disney screenwriter, Stanford University, National Public Radio, Huffington Post, a sodajerk, Michael Caine, the Taco Bell chihuahua, Penthouse, the London Times, Edinburgh Fringe Festival, a human guinea pig and Zippy the Chimp.

A free 20 minute consultation w/ the Book Doctors. We can change your publishing life in 2o minutes! We have helped hundreds of writers go from being talented amateurs to professionally published authors. Click here to buy & send proof of purchase to [email protected].

“You guys!! Thank you for that phenomenal all-day session at Stanford a few weeks ago. Can’t thank you enough for providing the most energizing and invigorating forum for getting us all in touch with The Writer Within.”

“I learned a lot about the publishing world but more about pitching my book. Prior to attending I had no idea what a pitch was. The feedback you provided was never derogatory, or demeaning you offered helpful and hopeful feedback. As a result I rewrote my own pitch and am hopeful. Thank you again.”

“I came to The Book Doctors with nothing but a dream. Now I have a book deal and I’m so excited & grateful.”

“By turns absurd, hilarious and tragic, Mort Morte tells the story of Mordechai Murgatroyd Morte, a young man who follows his mother through her unfortunate marriages to several physically and sexually abusive men.”

Buy the book here.

Interview from the Dan O’Brien Project

So begins MORT MORTE a macabre coming-of-age story full of butchered butchers, badly used Boy Scouts, blown-up Englishman, virginity-plucking cheerleaders, and many nice cups of tea.

So begins MORT MORTE a macabre coming-of-age story full of butchered butchers, badly used Boy Scouts, blown-up Englishman, virginity-plucking cheerleaders, and many nice cups of tea.WORD bookstore in Brooklyn is a fantastic bookstore. We had a lovely Art of the Novel event. Thanks to Jenn!

Here’s a new review for David Henry Sterry’s Mort Morte. To buy the book, click here.

“Mort Morte is a beautiful coming-of-age story that’s frequently laugh-out-loud hilarious.”

Originally published in Huffington Post.

Originally published in Huffington Post.

We first met Virginia Pye at the James River Writers Conference, one of the best writers conferences in America. If you’re a writer, do yourself a favor, get yourself to Richmond, Virginia and go to this conference. It’s filled with warm, generous, talented writers, editors and agents. When we first met Virginia Pye three years ago, she’d been writing and rewriting a novel for a very long time. It’s always exciting when you see a dedicated, talented writer who keeps evolving and changing and working, then finally gets their novel published, and actually gets lauded for it. So we thought we would check in with her to see exactly how it all happened.

The Book Doctors: Congratulations on being named an Indie Next Pick for your new novel, how did you feel when you found out?

Virginia Pye: I felt honored and excited, especially when I learned the other chosen authors, such as Caroline Leavitt, Benjamin Percy, Gail Godwin and Therese Anne Fowler. To be supported and encouraged by IndieBound booksellers means a lot to me. They’re smart and savvy book aficionados whose opinions I value. For years, I’ve read the books they recommend.

TBD: When did you start writing your book and why?

VP: Almost a decade ago as I helped my parents clear out their house, I came upon boxes of yellowed onion-skin pages with faint typescript on it. My grandfather, who was a missionary in northwestern China in the nineteen teens, had recorded his daily experience and impressions of that pre-industrialized, desolate, and yet eerily beautiful landscape. I’d always known about the roads, hospitals and schools that he had built in Shansi Province, but now I found his actual tally book in which he kept track of his converts. I felt both pride about his humanitarian successes and shame at his missionary zeal.

As I read his papers and studied the brown-tinged photographs, I was seated on an Oriental rug in the living room were I’d grown up–a room decorated with Chinese antiques and furniture. I was surrounded by my family’s history in China and I realized that, whether I liked it or not, part of my inheritance was a colonialist perspective on the world. I had not chosen it, nor felt that I shared it, but it was somehow mine to make peace with just the same.

The two main characters in my novel, the Reverend and his wife Grace, are upright, Midwestern missionaries who, over the course of their dramatic story find their faith tested and their world view shattered. It took some years for their story to fully emerge, but the germ for it began when I decided to wrestle with my grandfather’s legacy that I had previously tried to ignore.

TBD: What is your book about?

VP: On the windswept plains of northwestern China, Mongol bandits swoop down on the missionary couple and steal their small child. The Reverend sets out in search of the boy and becomes entangled in the rugged, corrupt landscape of opium dens, sly nomadic warlords and traveling circuses. He develops a following among the Chinese peasants who christen him Ghost Man for what they perceive as his otherworldly powers. Grace, his wife, pregnant with their second child, takes to her sick bed in the mission compound, where visions of her stolen child and lost husband beckon to her from across the plains. The foreign couple’s savvy, elderly Chinese servants, Ahcho and Mai Lin, eventually lead them on an odyssey back to one another and to a truer understanding of the world around them. River of Dust is a story of the clash of cultures and of retribution, and also of redemption. As the young American couple’s search for their child becomes more desperate, their adopted country comes to haunt them, changing not only what they believe but who they are.

TBD: You are involved with the James River Writers Conference, how did that community help you with the writing and selling of your book?

VP: James River Writers is a literary non-profit in Richmond, Virginia with around 400 members. I was chair of JRW for three years and on the board for close to a decade. JRW holds an annual conference each October, which is especially welcoming and friendly to writers of all types. I enjoyed working with everyone involved and made friends with many fellow aspiring writers, as well as the published authors and publishing professionals who came for the conference. Many of them were encouraging and offered to introduce me to their agents or fellow editors. JRW set a supportive and generous tone that I think everyone benefited from.

TBD: Did you hire an editor?

VP: For many years, I had worked on a previous novel that was about three generations of an American family with ties to China and Vietnam. It went through twenty-one drafts and dozens of agents saw it in various stages. They admired the writing and characters, but found that it just wasn’t quite working. Finally, I decided to take my manuscript to The Porches, a writing retreat in rural Virginia where I met author and editor, Nancy Zafris. She offered a different sort of editing experience from anyone else I’d heard of: she works with authors one-on-one over a weekend, discussing and brainstorming about the work. With Nancy’s perceptive questions, I began to see a new book emerging, one that was not a multi-generational story at all, but a compact and dramatic tale set in one year–1910–and in one setting–northwestern China. I left The Porches after that weekend with a new book in mind and a new, carefully conceived outline. I sat down on April 1st and completed a first draft on April 23rd. I had lived with the previous manuscript for so long– had wrestled with its problems and relished its strengths–that when it came time to write an altogether new version, I had enough previous connection to the characters and setting that the story came forth easily. It was both miraculous and not at all.

TBD: How did you find an agent?

VP: After I completed my marathon first draft of River of Dust, I shared it with Nancy who passed it along to her editor at Unbridled Books, Greg Michalson. He liked it and gave me a call. It was then that I realized I needed an agent. Gail Hochman had read the earlier multi-generational manuscript as well as another novel of mine. She had always been kind and thoughtful in her replies to my work, although she hadn’t taken me on as a client. I admired her authors–Michael Cunningham, Julia Glass, Ursula Hegi–so I chose to go back to her with River of Dust when Unbridled made their offer. I’m so glad I did. As everyone knows, Gail is a brilliant agent and an enthusiastic and caring person.

TBD: What are some of the mistakes you made as you wrote and tried to sell your book?

VP: In retrospect, I think that it may have been a mistake to work for so long on that previous novel. If something isn’t working, tinkering with it probably won’t help. To give myself more credit, I did revise–sometimes extensively–but I still wanted that manuscript to be the book I had in mind from the start. I was determined to bend the characters and plot to fit the book I envisioned. Somehow I wasn’t listening well enough to the voices of smart readers, or even my own voice that was whispering that it just wasn’t working. The manuscript was telling me that it needed to be altogether different. I was trying to write a book with a complicated structure before ever truly perfecting a simpler one. Perhaps there’s a lesson in that, too: succeed first at something smaller, before trying to tackle your opus. Come to think of it, I know a number of writers who have been working on big books for years and those projects never seem to come to fruition. Perhaps aiming for something less baroque and yet doing it well is a better way to go with a debut novel.

TBD: How do you plan to promote and market your book?

VP: I’ve written a number of essays about the backstory for my novel. “A Zealot and Poet,” about my grandfather, will appear in May in The Rumpus. I’m excited to be interviewed at Caroline Leavitt and David Abrams’s blogs and in The Nervous Breakdown. Excerpts from River of Dust will also soon appear in The Nervous Breakdown, and in The Collagist and DearReader.com. I had a great time creating a playlist for River of Dust for the Largehearted Boy. Unbridled has done a great job of setting up book events up and down the East Coast: in Richmond, Charlottesville, Alexandria and Norfolk, Virginia; New York, Boston and Western Massachusetts. I’m excited about all my events, but a few in particular stand out for me: a reading in the Lucian W. Pye Room at M.I.T. (named for my father who was a prominent Political Scientist there); a reading at Back Pages Books in Waltham, Massachusetts, at which my four closest high school girlfriends are coming in from around the country to cheer me on; and what I think will be a great evening at the China Institute in NYC, where I’m eager to share my work with China enthusiasts and experts and look forward to learning from my audience.

TBD: What are some of your favorite things about being a writer? And what are some of the things you hate about it?

VP: I am completely biased towards writers and writing. I think there’s nothing better to do with one’s life. OK, being a visual artist or musician is pretty good, too. And my husband is a contemporary art museum curator and that’s not half bad. But, as a writer, you have carte blanche to express your vision of the world, however quirky it may be. You can read voraciously and remain a dilettante. Aleksander Hemon recently said, “Expertise is the enemy of imagination.” As someone who has written a novel set in a country where I have never been, I agree. People ask if I did a lot of research before writing River of Dust. I did only as much as I needed to ignite my mind, which, as it turned out wasn’t a great deal–again, perhaps because I’d grown up with a visceral understanding of China passed down to me through two generations. I think that writers have an obligation to be thoughtful in their work. Good writing needs to offer meaning on several levels at once. A novel that has strong storytelling doesn’t need to sacrifice that goal. I hope that River of Dust is both a page-turner and an intelligent read. I love Philip Roth’s rallying cry to writers at his eightieth birthday and on the occasion of his retirement from writing: “This passion for specificity, for the hypnotic materiality of the world one is in is all but at the heart of the task to which every American novelist has been enjoined since Herman Melville and his whale and Mark Twain and his river: to discover the most arresting, evocative verbal depiction of every last American thing.” The only down side to writing is that it’s no easy task. But who ever wanted easy when trying to live a meaningful life?

TBD: I hate to ask you this, but what advice do you have for writers?

VP: Pay attention to the market: to what agents tell you at conferences and on Twitter; to what your independent bookseller says about the books he or she endorses; to what your most thoughtful and serious readers say about your manuscript. And then, put it all on the backburner while you write. Let it simmer in the back of your mind as you write the book you want to write. If their advice has resonated then it will help shape the next draft. Stick with the manuscript until it’s done and don’t start to shop it around too early. If you’re as eager as I was with numerous manuscripts, most likely you’ll shop it around too early. When you’ve written what you are truly proud of–after listening carefully for any hesitations and heeding them–reach out to agents and published authors with graciousness and gratitude. The publishing world is not waiting for you, but on the other hand, it can’t exist without you. So take up your rightful place, but politely and while keeping in mind that we’re incredibly lucky to be doing this thing that we love. At least, that’s how I try to approach it.

Virginia Pye’s debut novel, River of Dust, is an Indie Next Pick for May, 2013. Her award-winning short stories have appeared in numerous literary magazines. She holds an MFA from Sarah Lawrence, taught writing at New York University, and The University of Pennsylvania, and has helped run a literary non-profit in Richmond, Virginia. For more about her, visit: www.virginiapye.com

The Book Doctors have helped dozens and dozens of amateur writers become professionally published authors. They edit books and develop manuscripts, help writers develop a platform, and connect them with agents and publishers. Their book is The Essential Guide to Getting Your Book Published. Anyone who reads this article and buys the print version of this book gets a FREE 20 MINUTE CONSULTATION with proof of purchase (email: [email protected]). Arielle Eckstut is an agent-at-large at the Levine Greenberg Literary Agency, one of New York City’s most respected and successful agencies. Arielle is not only the author of seven books, but she also co-founded the iconic company, LittleMissMatched, and grew it from a tiny operation into a leading national brand that now has stores from Disneyland to Disney World to 5th Avenue in NYC. David Henry Sterry is the author of 15 books, a performer, muckraker, educator, and activist. His first memoir, Chicken, was an international bestseller, and has been translated into 10 languages. His anthology, Hos, Hookers, Call Girls and Rent Boys was featured on the front cover of the Sunday New York Times Book Review. The follow-up, Johns, Marks, Tricks and Chickenhawks, just came out. He has appeared on, acted with, written for, worked and/or presented at: Will Smith, Edinburgh Fringe Festival, Stanford University, National Public Radio, Penthouse, Michael Caine, the London Times, Playboy and Zippy the Chimp. His new illustrated novel is Mort Morte, a coming-of-age black comedy that’s kind of like Diary of a Wimpy Kid, as told by Travis Bickle from Taxi Driver. He loves any sport with balls, and his girls. www.davidhenrysterry To learn how not to pitch your book, click here.

Here’s a new review for David Henry Sterry’s Mort Morte. To buy the book, click here.

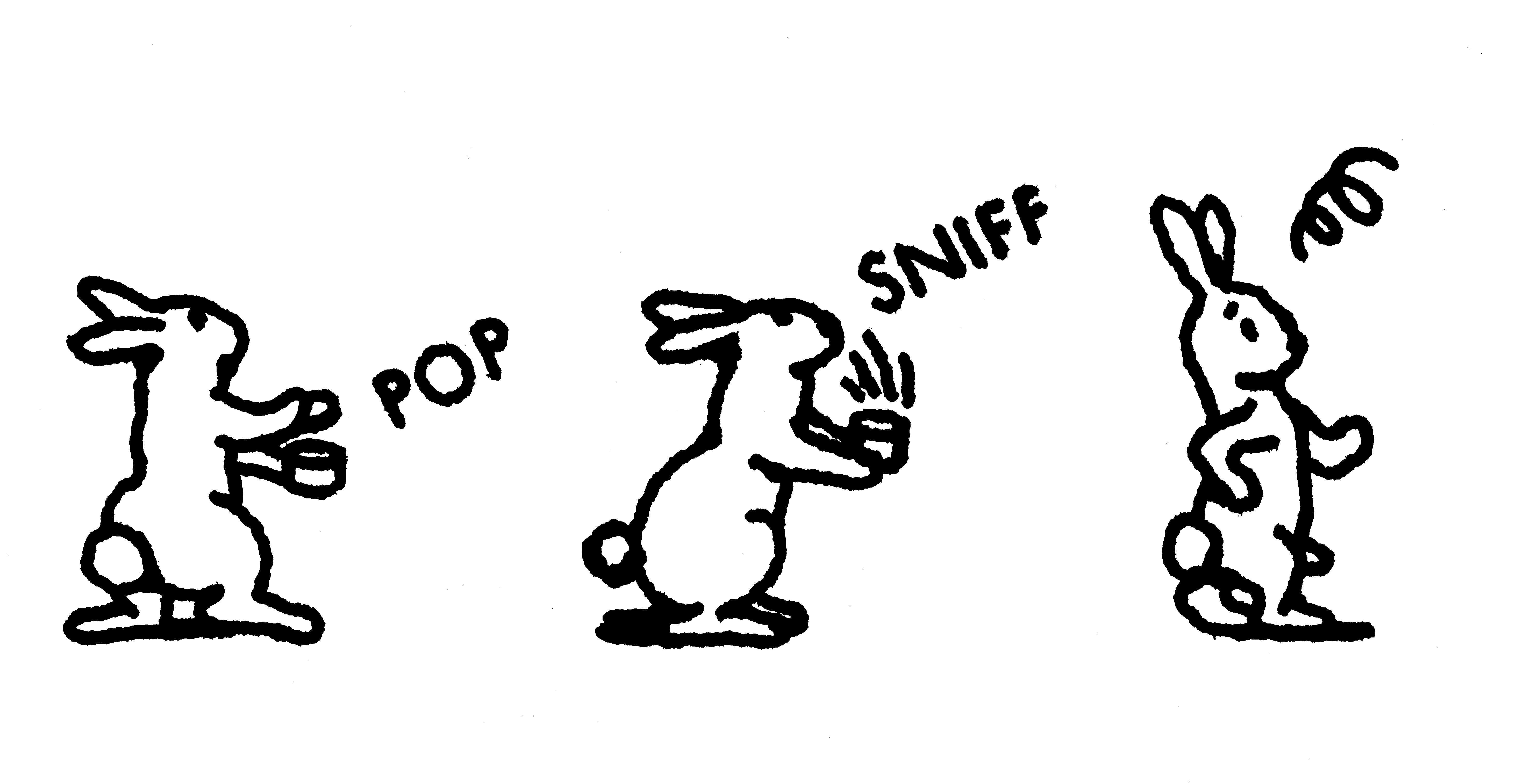

“Mort Morte by David Henry Sterry reads like an elegantly simple children’s book designed for adults. The chapters are rarely more than a page long and sometimes just a few words in length. While the format of the book is basic, with beautifully placed and executed illustrations by Alain Pilon, the story centers around adoration, violence, emotional, physical, and sexual abuse and revenge.

Mort Morte is a brutal coming-of-age story that’s frequently laugh-out-loud hilarious.

The narrator, Mordechai Murgatroid Morte provides a rollicking ride through the culture of a sophisticated and rough-and-tumble Texas with a dash of Harvard thrown in. Sterry’s use of the English language is masterful and sometimes whimsical, i.e. “The animal heads started spinning round faster and faster like I was on some kind of sick Taxidermilogical Tilt-A-Whirl….” At times Sterry’s writing is so raw it’s painful which is quickly eased by the guilty relieving pleasure of high humor.

Sterry has created a sympathetic character in Mort which is no easy challenge. Throughout his young life Mort suffers from fantastical anxiety dreams, he pulls rhythms and lyrics from melodies that mirror his moments of ecstacy, and at one point sums up his life “as a curious mixture of violent nausea and dizzying sexual fantasy.”

There’s a lot to like in this short, breezy book, notably its imaginative style and David Sterry’s love of language. No words are wasted here; Mort Morte succeeds mightily by saying a lot with a little.” – Liz Bulkley

“A lyrical roller coaster ride through the dark mind of a young serial killer. A post-modern fairy tale about what happens to a boy who is continually abused and bullied. The plot is surreal, but somehow all too real! I was quickly sucked in and enjoyed the book.” – Mateo

Caroline Leavitt On Overcoming Nasty Writing Teachers, How to Write a Bestseller and Never Giving Up

We first met Caroline Leavitt at the Miami Book Festival. If you ever have the chance to go to the Miami Book Festival, do yourself a favor and don’t pass up the opportunity. Not only is it one of the great international book festivals in the world, it’s also the kind of place you run into people like Caroline Leavitt. Not only is she an incredibly accomplished novelist, she’s also a crackerjack human being. Lots of writers tend to be shy at best — standoffish, churlish and surly at worst. Caroline is the exact opposite. She welcomes you with open arms. If you don’t believe me, just go to her Facebook page. It’s a continuous font of information, fun and love. And she’s also that rare bird who’s managed to somehow write literary novels that sell. So we decided to take a little peek into her world and see what makes Caroline Leavitt tick.

THE BOOK DOCTORS: How did you get into the book business to begin with?

CAROLINE LEAVITT: I was an outcast in suburbia with three big strikes against me: I was the only Jewish kid in a Christian neighborhood (my mother had to march up to the school to complain about a second grade test that asked questions about Jesus), I was sickly with asthma, and I was smart (only 10 percent of my high school went on to college. The rest joined the navy or got pregnant). I learned to live in books and I discovered I could keep myself from being beaten up by making up stories! The first time I told a story in front of the 5th grade and they didn’t throw spitballs at me or threaten me, I thought, how cool is this? This is what I want to do! But of course I heard no, no, no. When I got to Brandeis, I studied with this famous writer who told me I’d never make it. He used to slam my work in class while tears streaked my face, but I refused to leave the class. The day I published my first novel, I sent it, along with a rave NYT review to the professor, saying, “Hey, you were wrong.” He wrote back and said, “Oh, I just wanted to make you angry enough to keep pushing on.” I laughed and didn’t write back. I kept writing and writing and every week, those stupid self addressed stamped envelopes would bounce back with rejections. One day they came back and I ripped them both up into pieces. I happened to look down and there was one tiny, shining word: CONGRATULATIONS. I had sold a story and that story got me an agent, which got me my first novel.

TBD: What are some of the some of things you enjoy about writing?

CL: The fact that I can live other lives. The fact that I don’t have to dress coherently to do it. The fact that it keeps me sane. I write about what haunts me and I write the books I myself am dying to read. I love it. I can’t think of anything I’d rather do.

TBD: How do you turn off the voice in your head that says you suck?

CL: What makes you think I can? I can’t turn that voice off. It is always in my head. It always goads me to get online and compare myself to other writers. It pushes me into all sorts of magic thinking like tarot card spells and prayers to the universe: please don’t let me suck. My big revelation was one day when I got the best review I ever received in my life from the Cleveland Plain Dealer — they thought I was a genius! And then five minutes later, I got the worst review I ever received from the Phil. Inquirer who loathed everything the CPD had loved. I had a moment when I realized, not everyone is going to love me. I try to tell myself to go deeper, to just write and write and write about what matters to me, to not think about readers and critics or anything but the story. And I eat a lot of chocolate.

TBD: Do you ever get writer’s block, and if so would you do about it?

CL: I never get it. I’m always working and there’s never enough time!

TBD: Do you ever make decisions in your book based on what you think is going to make the book more commercially successful?

CL: Never. Not ever. You can’t second guess what is going to be commercially successful. You have to write the book you want to write. And wait, actually. My third novel, for a publisher that went out of business, I was pushed into writing a book that was “more commercially.” It got only two reviews, both of them so terrible I could barely leave my apartment for months, and the book died soon after. After that I vowed to never ever write anything I didn’t feel.

TBD: Do you outline your stories or do you make it up as you go?

CL: I’m big on story structure. I studied with John Truby, who mapped out story by means of moral wants and needs, and that’s what I do. Hey, so does John Irving.

TBD: Do you finish the whole draft before you go back and edit, or do you edit as you go?

CL: I do both. I edit as I go, and I must do about ten thousand drafts. Well, more like 23. And I’m serious about that.

I love rewriting because that is where and how you discover the story. It’s like you have this skeleton and you get to put flesh on it and hair and clothes and really wonderful jewelry.

TBD: You have such a fun Facebook life, what is your guiding principle in social media?

CL: Being honest. You can tell when people are trying to do what they think they should do. I’m intensely curious about everyone’s lives and I want to get to know a lot of people. I also don’t hesitate to say how I feel or what’s going on. I am who I am. (Popeye 101) I spend so much time every day alone and writing, that social media is my water cooler. I crave contact.

TBD: Were you working on right now?

CL: My novel Is This Tomorrow, about a 1950s suburb, paranoia and a vanished child, is coming out in May, so I’m doing all this prepublicity type stuff, and I sold my next novel, Cruel Beautiful World (thanks to my 16-year-old for the title!), to Algonquin on the basis of a first chapter and an outline. So I’m writing that now, deeply immersed in that moment in when the ’60s turned into the ’70s and things got ugly.

TBD: Where you see the future of books going?

CL: I think it’s going to boom. People love stories. They need stories. More people are reading on ereaders. I know a few NYT bestsellers who self-published their next book to have more control. Maybe I’m stupidly optimistic but I can’t imagine a world without books.

TBD: I hate to do this to you, but you have any advice for writers?

CL: Yep. Never ever give up. Don’t listen to all the no’s but keep writing. Keep writing. My career was over, so I thought, when my ninth novel, Pictures of You, was rejected by my then publisher as not being “special enough.” I had no sales. No one knew who I was. I called all my friends in tears and one suggested her editor at Algonquin. So I wrote up a paragraph about the book and sent it to her. She liked it and a few weeks later, she bought it and all of Algonquin was doing the unthinkable–the thing that had never happened to me–treating me with respect. They took that unspecial book and turned it into a NYT bestseller and a USA Today ebook bestseller and it got on the Best Books of 2011 lists from the San Francisco Chronicle, the Providence Journal, Bookmarks Magazine and Kirkus Review. I feel like I’m the poster girl for second chances.

Caroline Leavitt is the author of many novels, several of which have been optioned for film, translated into different languages, and condensed in magazines. Her ninth novel, Pictures of You, was a New York Times bestseller, and was also on the Best Books of 2011 lists from the San Francisco Chronicle, the Providence Journal, Bookmarks Magazine and Kirkus Reviews. Her new novel, Is This Tomorrow, will be published May 2013 by Algonquin Books. Cruel Beautiful World will be published sometimes in 2015 by Algonquin. Her essays, stories, book reviews and articles have appeared in Modern Love in the New York Times, Salon, Psychology Today, the New York Times Sunday Book Review, People, Real Simple, New York Magazine, the San Francisco Chronicle, Parenting, the Chicago Tribune, Parents, Redbook, the Washington Post, the Boston Globe and numerous anthologies. She won First Prize in Redbook Magazine’s Young Writers Contest, was a 1990 New York Foundation of the Arts Award, a National Magazine Award nominee for personal essay, and is a recent first-round finalist in the Sundance Screenwriting Lab competition for her script of Is This Tomorrow. She teaches novel-writing online at both Stanford University and UCLA, as well as working with writers privately. She lives in Hoboken, New Jersey, New York City’s unofficial sixth borough, with her husband, the writer Jeff Tamarkin, and their teenage son Max.

My first piece on Salon. Thanks to Arielle Eckstut. To read on Salon click here: http://www.salon.com/2013/02/14/i_wrote_my_way_to_true_love/

“You should stop writing these stupid movie scripts and write about your life, it’s so much more interesting.” Janine, my hypnotherapist, was not being unkind. She just had no filter. And she was right. That was the most infuriating thing about Janine my hypnotherapist. She was always right.

I had just gotten a three-picture deal with Disney. Well, it wasn’t really a three-picture deal. They hired me to write a script for one of their moronic ideas (Sinbad in the Army with dogs), and in the contract they locked me up for another two movies for slightly more money each time. But at the bottom of every page was writ in small letters: “We can terminate this contract for any reason at any time for perpetuity and eternity in this and every other conceivable universe and pay you NOTHING.” I asked my agent and she said I could tell everybody I had a three-picture deal with Disney. Even though I didn’t really. And that, in a nutshell, is Hollywood, baby.

But the thought of telling the truth about myself made me hot and clammy, sticky and jittery, teeth tearing into cuticles till they bled. I was much more comfortable working on my buddy script about two 12-year-olds who go to Vegas and beat the mob. Or my mobster-becomes-a-vampire script. Or my “Some Like It Hot” cross-dressing baseball script.

But I’d always wanted to write a book. So that night I started writing one. It was liberating. Gave my obsessive mind something to focus on besides my own sex-addicted self-loathing.

Turns out I wasn’t quite ready to tell that story yet. I hadn’t hit bottom. I was still living in my beautiful Craftsman home in the hills of Echo Park with my beautiful red sports car and my beautiful sex-denying fiancée. I hadn’t yet been fired by Disney, my Sinbad/Army/dog script unmade, my fictitious three-picture deal evaporated in a puff of smoke. I hadn’t yet been dumped by an entirely different beautiful damaged narcissistic sex-denying fiancée whom I DIDN’T EVEN LIKE. I hadn’t yet been whacked over the head with a metal pipe at 4 a.m. in Harlem by an angry disenfranchised crackhead while pursuing a transsexual thief masquerading as a female sex worker. That was when I hit bottom. The bottom of the bottom.

David Henry Sterry is the author of 14 books, including his memoir, “Chicken,” an international bestseller that has been translated into 10 languages. His anthology, “Hos, Hookers, Call Girls and Rent Boys,” was featured on the front cover of the Sunday New York Times Book Review. His new illustrated novel is “Mort Morte,” a coming-of-age black comedy about gun violence and children, and a boy who really loves his mother.

I’m proud to announce that the first book I ever wrote, which I started 20 years ago, is finally coming out. I’m very proud of this book, and the sublime illustrations by one of my favorite artists, Alain Pilon. But perhaps more importantly, this is the book that led me to the love of my life. To read the story behind that, click here it’s my first story on the wonderful website Salon. To see the video trailer, click here. To buy the book, click here.

On my third birthday, my father, in an attempt to get me to stop sucking my thumb, gave me a gun. “Today son, you are a man,” he said, snatching the little blue binky from my little pink hand. So I shot him.

So begins MORT MORTE a macabre coming-of-age story full of butchered butchers, badly used Boy Scouts, blown-up Englishman, virginity-plucking cheerleaders, and many nice cups of tea.

Poignantly poetic, hypnotically hysterical, sweetly surreal, and chock full of the blackest comedy, MORT MORTE is like Lewis Carrol having brunch with the kid from The Tin Drum and Oedipus, just before he plucks his eyes out.

In the end though, MORT MORTE is a story about a boy who really loves his mother.