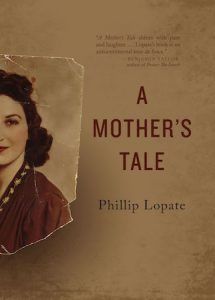

Phillip Lopate is one of the smartest guys we know–about books, about words, about literature, and, frankly, about life. So when we found out he had a new memoir coming out called A Mother’s Tale, we thought we’d pick his brain about why words and mothers matter.

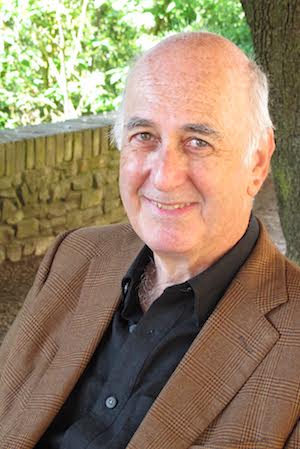

Phillip Lopate

The Book Doctors: What were some of your favorite books and authors as a kid, and why?

Phillip Lopate: As a kid, I was drawn to Robert Louis Stevenson’s Kidnapped, books about Greek mythology, and just about any nonfiction young adult book about baseball. I was not a very selective reader; I read just about everything in my local library. Taste came later.

TBD: How did you become a writer? Can someone actually learn to write, or are some people just born writers?

PL: I initially thought I was not smart enough to become a writer, but experimented with story-writing for my own amusement. I was the editor of my high school and my college literary magazine, which required a certain amount of posing and bluffing. Mostly what I was was a reader. I worshiped at the altar of literature. I do think it helps to have talent, but persistence matters more. Writers are made, not born.

TBD: Why did you choose to work with a university press for this book, which doesn’t seem inherently academic? We’re interested in the change in academic presses over the years and wondered if you could share your observations.

PL: I chose a university press because, frankly, a bunch of commercial presses passed on the manuscript, saying they weren’t sure how to sell it. Then I found out that Ohio State University Press was starting a new nonfiction/essay imprint, and I submitted it to them and they were happy to snap it up. You have to find a publisher who will love your book, whether it’s a trade or academic press. In these days when publishers are under so much pressure to make money, the line between commercial, academic and small independent presses is very thin. Any port in a storm, as they say.

The Ohio State University Press

TBD: You wrote, “I was put on earth to understand my mother’s pain I have not gotten very far in the process.” I feel much the same. What did you learn about her pain writing A Mother’s Tale?

PL: I learned a lot about my mother’s range, and her alternation between being very shrewd and self-deluded. As for her pain, some people find tremendous animation in self-pity and rage: there’s not a lot you can do about it.

TBD: Does writing help you understand things you don’t know about yourself, other people, and the world?

PL: Writing certainly helps to understand myself better, as well as other people. I have only to start to explain something I’ve thought or done and I begin to get a whiff of defensiveness and alibi-ing. I just have to talk to myself on the page. Essays are perfect for that kind of back-and-forth, with a drive toward greater honesty.

TBD: I tried to talk with my mother about sex with very little success. What was it like hearing your mom talk about her sexuality?

PL: I cannot say it was much fun as her son hearing my mother talk about her sexuality. But in retrospect, I’m glad for her expressiveness and lack of self-censoring. I think it helped me to become a writer, and to appreciate that things are what they are.

TBD: Family secrets and lies seem to be a universal fact of life. What did you find out about yours?

PL: There is no getting around family secrets: every family has them. I learned a little more about my mother’s affairs and how my father responded to them. I also learned how my mother fit into her historical period, how she reacted to the big public events of the day.

TBD: Your mother seems to be such a larger-than-life character. How did her melodrama affect your personality development?

PL: My mother’s melodramatic temperament pushed me in the opposite direction: I became skeptical of Drama, and a bit clinical and detached. A spectator, in effect, with an aversion to tantrums.

TBD: How would you characterize the book’s genre?

PL: I would say it’s like a play, a dialogue between my mother and my younger self, with my present, older self commenting and kibbitzing.

TBD: We hate to ask you this, but what advice do you have for writers?

PL: Read a ton, and put in a thousand hours at your desk. Don’t get discouraged by what nay-sayers tell you. You’ll know when you’ve hit pay dirt.

Phillip Lopate is a central figure in the resurgence of the American essay, both through his best-selling anthology The Art of the Personal Essay and his collections Bachelorhood, Against Joie de Vivre, Portrait of My Body, Portrait Inside My Head and To Show and to Tell: The Craft of Literary Nonfiction. He directs the nonfiction MFA program at Columbia University, where he is Professor of Writing.

Arielle Eckstut and David Henry Sterry are co-founders of The Book Doctors, a company that has helped countless authors get their books published. They are co-authors of The Essential Guide to Getting Your Book Published: How To Write It, Sell It, and Market It… Successfully (Workman, 2015). They are also book editors, and between them they have authored 25 books, and appeared on National Public Radio, the London Times, and the front cover of the Sunday New York Times Book Review.