Anna Staniszewski is one of our daughter’s favorite authors. Our daughter is nine, with great taste in books, so we always pay very close attention to who she’s loving as a middle grade reader. We were all lucky enough to meet Anna at least year’s New England SCBWI Conference and had the chance to pick her brain after about writing, writers, MFA programs, kids’ books, and whatever else spilled out of our collective heads.

Read this interview on the HuffPost.

Anna Staniszewski

The Book Doctors: I’d like to start with the MFA programs, because we hear such conflicting things, particularly for children’s book writers. What are the benefits of going to a program like the one at Simmons College where you teach?

Anna Staniszewski: I hear that question a lot. For me, I think that it comes down to two things. If you want to be a published writer, you have to put in the work. Some people need a structured environment like an MFA program. I know I did. For other people, they can do it on their own. Another benefit of having an MFA program is the community aspect of it. You have this network that you’re part of—people with similar interests and goals. Some say you can’t be taught to write. While I think ultimately the actual storytelling voice is hard to teach, I obviously believe that you can teach someone to write, because I attended an MFA program and I teach in one.

TBD: What kinds of things do you actual teach in an MFA program for children’s literature?

AS: When the students come into the MFA program at Simmons, we really break down the basics. We look at character, plot, structure, setting, all those things, which seem really basic because we do so many of them by instinct, because we see how they work in other people’s stories. But if you really break down how they work, then you can take them and use them in your own story. The more aware you are of the different building blocks of fiction, the more consciously you can use them to benefit the story that you’re working on.

TBD: What was the transition like going from student to published author to teacher?

AS: When I first started at Simmons, I originally went for the MA of Children’s Literature. I wasn’t quite sure what I wanted to do. I thought I wanted to go into publishing. But my first semester there they were just launching that MFA program–this was over ten years ago–and so I thought that’s exactly what I want to do, I want to do both those things. Once I knew that, I was really focused throughout that program on wanting to be published when I graduated, and then when I finished, I actually applied to the Writer Resident Program at the Boston Public Library and, miraculously, got it the next year. Right after I graduated I was a writer-in-residence at the BPL, which was amazing. I think that really gave me such a boost of confidence that writing could be a real job for me! Right after I finished at the BPL, I went to teaching. Originally, for the first year that I taught, I taught all over the Boston area. I was really lucky when an opening popped up in Simmons, where they needed someone to teach in the MFA program, so I was able to do that right around the time that I got my agent. That was interesting to go through the submission process all while I was teaching other students who were trying to get to the same point.

TBD: One thing that we run into all the time is that people think that it is easier to write a children’s book than an adult book, particularly when it comes to picture books, and what I find amusing, in terms of length of time, is that it takes longer to publish a picture book than it does any other kind of book that I’ve ever seen.

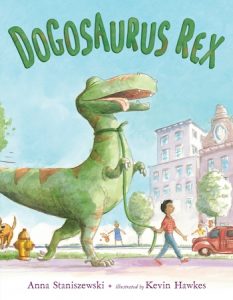

AS: Absolutely! I sold my first picture book in 2011, and it is coming out in 2017. It was a long process! (Even though book publishing is a slow process, it’s rare for a book to take this long.) I think because there are so few words, you have to pick the exact, perfect words for every spread. And then there’s this whole other element if you’re not the illustrator and you just have to wait and hope that it all comes together! Writing picture books is such a specific craft, I was actually a little bit intimidated by it for a while. For me, writing a novel somehow feels less scary.

Holt Books for Young Readers

TBD: For those writers out there who really know nothing about the craft of picture books, do you have a few tips?

AS: I would say the big thing is thinking about what would you like to see illustrated because I think a lot of times you’ll have a certain idea of “wouldn’t this be cute” and “wouldn’t this be fun,” but then you really have to think, “Can I get several illustrations out of this?” Then there are the parts of your book that not only could be illustrated, but also are begging to be illustrated! That’s why you need to find an idea that doesn’t just resonate with people, but that’s demanding to be illustrated.

The other thing I often tell students, because this is true of my own experience, is that an idea is not a story. The picture book I mentioned that’s coming out in 2017–the one that took six years–that was one where it took me a good year to find what I was actually trying to say. I came up with the idea, “Oh, wouldn’t it be fun if a boy turned a dog into a dinosaur?” And so I kind of played around with it, and it just wasn’t really working. I think part of it was because I wasn’t really thinking about the illustration potential. But I think a bigger part of it was that while it was a fun idea, it wasn’t really a story. And so I had to really dig into it. It took me a while to find what it needed to be about, which was the relationship between the boy and what turned out to be just a dinosaur.

Probably the most important thing in a picture book is the emotional component to the story. Because picture books are so short, there’s so little time to get the point across. You need something readers can really connect to on an emotional level because otherwise it’s just a fun story and you forget about it. But if there’s that deeper emotional layer, then readers will come back to it over and over.

TBD: We love that last one! We do a lot of work with writers to try to help them figure out how to pitch their books, and many writers have tremendous difficulties doing this. We get so many pitches where we don’t see an emotional connection with their main character. They just have an idea, there’s no actual plot or story there.

AS: It’s true, because by the time you finish reading a story, if there’s no emotional component and there’s no real plot, you find yourself asking, “Why did I just read this?” There has to be something there, even if it’s not a traditional story arc. My picture book, Power Down, Little Robot, is not a traditional story arc. It’s about a robot that doesn’t want to go to bed. It tries out all these different things to prevent going to bed, so it’s more like a list-type story. But I really try to highlight the mother-son relationship there. I hope, by the end, readers feel changed by the story, even if it doesn’t have a traditional beginning, middle, and end.

TBD: It’s confusing to many people who are starting out in the field what the category Middle Grade even means–the age range, where it diverges from early reader, how it stretches up to YA but doesn’t cross over into it. Can you give us your thoughts on this?

AS: I get this question all the time as well. I think people define it slightly differently, but this is how I think about it. I think the characters are typically between the ages of eight and twelve or thirteen. There are also early chapter books, and I do include those in early middle-grade, so in early chapter books, the protagonist can sometimes be in second grade or age seven. But a lot of early readers of chapter books are very much riding that line between picture book and novel. So I look at early chapter books on a case-by-case basis to know where exactly those fall. I feel like once you get into high school, that’s where it gets tougher. In my novels, most of my characters are thirteen or fourteen, which is at the upper end of middle-grade, often referred to as “tweens.” And even fifteen years ago, those would have been published as YA. Because YA has aged up so much, middle-grade has had to expand a little bit and the characters have become a little older.

While part of the way I define middle grade is by age, part of it I define by focus. It’s not only the content, but also how you deal with the content. So in middle-grade, if it’s younger middle grade, you might get away with a little bit of romance, but there are a lot of kids who don’t want that in their books. Whereas if it’s upper middle-grade, you might see a little bit of romance and you might see some darker things like war and death. With the latter, they tend to be handled a little bit more in the background or off-screen, so they are certainly there and they’re impacting the main character, but not in a direct way. For example, if there’s a character with something very serious going on in her life, maybe that’s not happening to the main character, it’s happening to the main character’s friend or somebody else in the family. In middle grade, you’re still kind of discovering what the world is like, whereas in young adult, I’d say it’s “Now that I know what the world is like, how do I fit in?” In YA, the focus is more inward, where middle-grade is more outward.

TBD: In your bio you write, “When she’s not writing, Anna spends her time reading, daydreaming, and challenging unicorns to games of hopscotch.” We thought this was so funny, and it’s just the sort of thing our nine-year-old daughter would love. Speaking of our nine-year-old daughter, she loves your books so much and just had the experience where she sat down with The Dirt Diary and couldn’t get up until she finished. You captured something that felt grounded in reality yet she could fantasize. How do you come up with your stories? Are they things that just come to you, or are they things you’ve been thinking about since you were little?

AS: I feel that I never have a lack of ideas. I feel like my brain is open, that it’s always asking “What if this happened?” I’m always kind of twisting the things that I notice, and thinking about “What if I told it this way?” Then it’s just a matter of figuring out what am I most excited about, and that’s what I decide to write about. But sometimes I feel like the process is a little bit mysterious. With my first book, My Very UnFairy Tale Life, I was working on something completely different. I was working on a sort of depressing book that ended up not going anywhere, and I needed something fun to work on. So I sat down and I just thought “Okay, I’ll just write a fun scene, just for myself,” and I wrote a scene about a girl who came home from school to find a talking frog sitting on her bed, and if that was me, I would have screamed and run out of the room, but she was so annoyed at the sight of the frog, and she actually grabbed that frog and she threw it out a window. I thought, “Who is this character? I need to know more about her!” I would write a chapter or two every once in a while, just for my own amusement, and that’s how that book came about. With my book The Dirt Diary, I heard a story on the radio about a girl who used to work for her mom’s cleaning business and a bell went off in my head. So for me, the premise comes first a lot of times, but it’s not until I connect with the characters that I go with it.

I feel that what you were saying about being rooted in the real world with a little bit of fantasy or magic, those are the kinds of stories I’ve always loved the most, and so I feel like that’s what I most enjoy writing as well.

TBD: We were impressed with how you dealt with class issues in The Dirt Diary. Our daughter happens to be in a public school that is very mixed, class-wise, from the very top to the very bottom. We were happy to see her reading a book that made her think about class. Speaking of which, your dedication may be our favorite ever: To anyone who has ever had to clean a toilet.

AS: I always thought I’d write fantasy. I wasn’t sure I had realistic fiction in me until I started writing it. For me, I guess what helped me was that I felt like my entire middle school existence could be summed up in the word “embarrassed.” I was nothing but embarrassed all the time. I also needed to know “Where do I fit in?” So a lot of those class issues are things that I experienced in school, where there were kids who lived in the big fancy houses and their families had big fancy cars, and then there were the rest of us. There was a lot of pressure no matter where you were on that hierarchy, and I thought that was something worth exploring. It also felt very true to my character because of the situation I put her in, and it also felt very true emotionally for me. A lot of people ask me how much of that story comes from my personal experience, and it’s very little. I did not clean houses for a living. I try to avoid cleaning houses at all, even my own. But I feel the emotional element is very true to life, and so I feel like I took a character who is very shy and very awkward, and took those qualities from myself when I was her age and amplified them by ten.

TBD: Something we run into every day with clients trying to get children’s books published is the desire tell us what their book is trying to teach. I would love for you to say something about the didactic nature of children’s books, and what do you advise on that?

AS: I think the important thing is telling a good story, and if there’s something that comes out of that for the reader, that’s fantastic, but if that’s the aim–if you go into it looking to teach something—it will show. The story always has to come first. When I set out to write a book, I’m not thinking what I want the reader to learn, or what do I want the character to learn, I just focus on something much more simple, like how does the character change. I try to think of it in a very specific way. With The Dirt Diary, for example, it’s about a character finding her voice. Though that may imply that maybe she learned some things along the way, that’s not what the story is really about. I think about: “Where does she start?” She’s shy, she can’t speak up for herself. “Where does she end?” She comes out of her shell a little bit, she speaks up for herself, at least when she really needs to. I’m not just trying to hit the reader over the head with a lesson or a moral. As a reader, I like to be able to think about the book myself and also feel like I have grown and changed along with the character; that’s more valuable than having a very obvious and concrete lesson.

Anna Staniszewski is the author of several tween novels, including The Dirt Diary and Once Upon a Cruise, and the picture books Power Down, Little Robot and Dogosaurus Rex. She lives outside of Boston and teaches at Simmons College. When she’s not writing, Anna spends her time reading, daydreaming, and challenging unicorns to games of hopscotch. You can learn more about her and her books at www.annastan.com.

Arielle Eckstut and David Henry Sterry are co-founders of The Book Doctors, a company that has helped countless authors get their books published. They are co-authors of The Essential Guide to Getting Your Book Published: How To Write It, Sell It, and Market It… Successfully (Workman, 2015). They are also book editors, and between them they have authored 25 books, and appeared on National Public Radio, the London Times, and the front cover of the Sunday New York Times Book Review.