We first met Tami Charles at a Pitchapalooza at the great independent bookstore, Word, in Jersey City; and we immediately knew she was a star. We met her again a year or so later at a book reading by Arielle’s Newbery-Award-winning client, Kwame Alexander, where we got the news that Tami had landed a book deal. Just another reason to go to awesome author’s events! Tami carries herself with such style and was so articulate, funny, and altogether together, we immediately thought she was a person who would succeed in any business. And it turns out she has, in the business of books. We found out she had a book coming out, and now that it has arrived, we decided to pick her brain about what it takes to get published when you write for kids.

Tami Charles

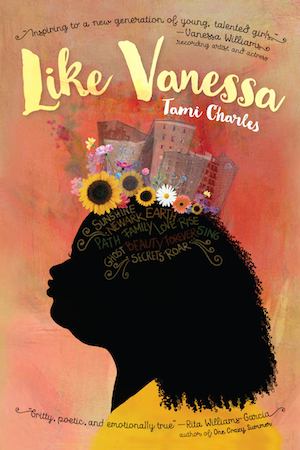

Tami CharlesThe Book Doctors: Tell us about your debut novel Like Vanessa.

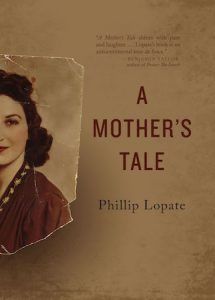

Tami Charles: Thirteen-year-old Vanessa Martin has always watched the Miss America pageant with her Pop Pop. Even though she often dreamt of herself on that stage, she’d never seen a woman of color win. That all changes on September 17, 1983, when Vanessa Williams makes history as the first black woman to capture the title. That sets young Vanessa on her own path to enter her school’s beauty contest. Problem is, her father and the resident mean girl think she doesn’t stand a chance.

TBD: How did you get a big star like Vanessa Williams, who is the Vanessa in the title, Like Vanessa, to give you a blurb?

TC: A little bit of luck and a whole lot of blessings! Vanessa Williams is a former Miss America. She’s the reason why I participated in the Miss America program while in high school. So it was natural that I reached out to fellow pageant friends (and my writing community) for advice on ways to connect with her. Luck would have it that she was holding a show at a local theater and after pitching the novel to her agent, I was granted a meeting with her after her performance. I gave Ms. Williams a copy of the novel, we chatted a bit, and took some pictures. I kept in touch over the course of a few months and was honored to receive a glowing endorsement from her for the novel’s cover.

TBD: Tell us about your path to publishing Like Vanessa?

TC: Like Vanessa was not my first book. I’d written quite a few others and had gotten rejections galore. After taking some time to work on my craft, I began creating this novel, which had been an idea in my head for years. I wrote Like Vanessa during National Novel Writing Month (Nanowrimo) of 2013, edited it through the winter, shared it with my critique group, hired an editorial consultant to prepare it for submission, and then started querying in spring, 2014. I was super thrilled to land my agent, Lara Perkins of Andrea Brown Literary, with this manuscript. Together, we edited some more and went out on submission to publishers. To my surprise, I landed a two-book contract at Charlesbridge Publishing, with the fabulous Karen Boss serving as editor.

TBD: You also do picture books. How did you hook up with a great publisher like Candlewick?

TC: I love writing picture books and Freedom Soup was actually my very first book deal, even though Like Vanessa published first. My agent pitched the book to an editor at a different publishing house. While the editor liked the story’s concept, she felt there was someone else better suited for it, given his love of Haiti. Carter Hasegawa at Candlewick made an offer on my debut picture book and it’s been great working with him. We even have another picture book together entitled A Day With The Panye, publishing in 2020.

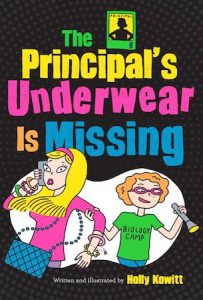

TBD: Tell us about the Daphne books.

TC: In front of her followers, Daphne is a hilarious, on-the-rise vlog star. But at school, Daphne is the ever-skeptical Annabelle Louis, seventh-grade super geek and perennial new kid. To cope with her mom’s upcoming military assignment in Afghanistan and her start at a brand new middle school, Annabelle’s parents send her to a therapist. Dr. Varma insists Annabelle try stepping out of her comfort zone, hoping it will give her the confidence to make friends, which she’ll definitely need once Mom is gone. Luckily there is one part of the assignment Annabelle DOES enjoy — her vlog, Daphne Doesn’t, in which she appears undercover and gives hilarious takes on activities she thinks are a waste of time. She is great at entertaining her YouTube fans, but her classmates don’t know she exists. Can Annabelle keep up the double life forever?

TBD: Why should a writer whose writing books for kids join SCBWI?

TC: The reasons are endless. SCBWI provides a sense of community for writers of all levels. I have met some of the kindest, most helpful writers because of this organization. We have critiqued each other’s work, provided a shoulder to cry on during times of rejection, and raised our pom poms to celebrate industry milestones. Also, the opportunity to meet and learn from powerhouse agents, editors, and art directors at conferences is priceless.

TBD: How did you get on Good Morning America?

TC: Again, a little luck and a huge dash of sisterhood! A pageant friend who coordinates bookings for Good Morning America posted on Facebook that she was looking for home cooks to feature on a Thanksgiving segment. I dub myself a wannabe chef, plus my debut picture book, Freedom Soup, is about a traditional Haitian holiday meal (bonus recipe included), so I had to take a chance. I provided my recipe and an audition video and got a call, asking to appear on the show. I had the time of my life and hope to do more television segments in the future!

TBD: What’s the key to a writer making a video?

TC: I’m not sure that I’m the expert here, as I still have my training wheels on. I’ll say this: just be yourself and have fun. Authenticity is what will connect you to potential readers.

TBD: How are writing and getting published different when writing picture books, middle grade and young adult books?

TC: There isn’t much difference between the three, I’d say. Maybe on the logistics end, since middle grade and YA books are longer. With picture books, the word count is much shorter, but there’s a lot to consider, especially with leaving room for the illustrator to shine. That’s not the easiest task!

TBD: Who inspires you?

TC: This is a trick question! I could take up pages on this one, so I’ll try and keep it short: My family, particularly my husband and son, and countless writers fighting the good fight with the words and art they put on the page: Kwame Alexander, Rita Williams-Garcia, Guadalupe Garcia McCall, Meg Medina, Edwidge Danticat, Toni Morrison, Maya Angelou, Vanessa Brantley-Newton, Floyd Cooper, Margarita Engle, okay I’ll pause here. But yeah, these folks give me hope!

TBD: We hate to ask you this, but what advice do you have for other writers?

TC: Blinders on! There’s no time to worry about what other folks are doing. Their success will look different than yours and you certainly can’t measure yourself against them. Success comes in all forms. You wrote a paragraph today? Celebrate that. Got a six-figure book deal? Good for you! Starting to get “nicer” rejections? Don’t worry. Your “yes” is coming. Hold the vision you have for yourself and trust that with razor-sharp focus, you’ll get there.

You can follow Tami Charles on Twitter @TamiWritesStuff, Instagram @tamiwrites, or her website: www.tamiwrites.com.

Check out the inspiration behind Like Vanessa here:

Tami Charles: Former teacher. Wannabe chef. Debut author. Tami Charles writes picture books, middle grade, young adult, and nonfiction. Her middle-grade novel, LIKE VANESSA, has earned Top 10 spots on the Indies Introduce and Spring Kids’ Next lists, along with three starred reviews. Her picture book, FREEDOM SOUP, debuts with Candlewick Press in fall, 2019. She also has more books forthcoming with Capstone, Sterling, and Albert Whitman. Tami is represented by Lara Perkins, of the Andrea Brown Literary Agency.

Arielle Eckstut and David Henry Sterry are co-founders of The Book Doctors, a company that has helped countless authors get their books published. They are co-authors of The Essential Guide to Getting Your Book Published: How To Write It, Sell It, and Market It… Successfully (Workman, 2015). They are also book editors, and between them, they have authored 25 books and appeared on National Public Radio, the London Times, and the front cover of the Sunday New York Times Book Review. Get publishing tips delivered to your inbox every month.

JOIN THE BOOK REPORT TO RECEIVE MORE INTERVIEWS AND TIPS ON HOW TO GET PUBLISHED!

Arielle Eckstut & David Henry Sterry have helped hundreds or writers get successfully published. They wrote The Essential Guide to Getting Your Book Published.