We live in Montclair, New Jersey. John Dufresne lives in southern Florida. So naturally, we met him at the South Dakota Festival of Books. We were sitting next to him waiting for people to show up to sign our books. Let’s just say there wasn’t a huge line. Normally, this would really be a downer, but this time we realized it was good luck because we got the chance to talk with John.

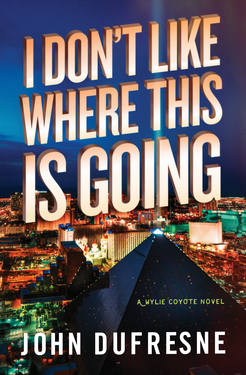

John has had a long and distinguished career as a writer. He also teaches writing. Now that his new book, I Don’t Like Where This Is Going, is out, we picked his brain about writing, books, publishing, and life.

To read the full interview on the Huffington Post, click here.

The Book Doctors: When did you first start becoming a writer, and how did you learn to be one?

John Dufresne: I was a storyteller first, even if I didn’t know I was. My father told me a bedtime story every night. Fairy tales. Only I thought he made them up because he had no book. I thought he invented wolves. He may be why I loved stories and wanted to make up my own. I had a couple of narratives going when I was seven or eight or so in which I was the central character. They both took place in my neighborhood. In one I was the leader of a band of good guys with white hats and spirited horses. Cowboys on Grafton Hill in Worcester, Mass. The only real horse we ever saw on the Hill was the ragman’s nag, whom we loved to pat. Every night in bed I continued the story from where it ended when I had dozed off the night before. I did this for years. And during the day, I was thinking of what I would now call plot points and creating new characters. The other narrative was similar with me as a sports hero. Whenever I heard sirens, I imagined the house the fire trucks were heading for and the people trapped inside the burning house and how they would be saved. Or not.

TBD: What were some of your favorite books as a kid, and why?

JD: I grew up in a house without very many books. We did have 26-volumes of the Universal Standard Encyclopedia, bought for 99 cents a week at the A&P on Grafton Street. I read them in order, not quite thoroughly. One month every subject I talked about at the supper table began with A. Afghanistan, alligator, antbirds. With volume 13, it was everything between Idaho and Jewel Cave. I loved information, loved knowing the names of things. I didn’t much like the stories we read in my grammar school, stories about kids who had horses and good fortune. I couldn’t find anyone like me, someone who grew up in a housing project, in them. Then I happened on a series of books that I devoured, the Chip Hilton series for boys, written by Claire Bee. I think it was David Mamet who described drama as two outs, bottom of the ninth, man on first, 3-2 count, and your team down by one. That describes Clutch Hitter, a book in the series that illustrated to me, the little jock that I was, how exciting, compelling, and tense a story could be.

TBD: Your new book, I Don’t Like Where This Is Going, is a wild, wacky ride that fits squarely into the noir tradition, but it seems to break as many rules as it follows. How did you get the idea for the book, and does writing in this genre inform how you work?

JD: I found a character I liked in a short story I wrote. I wrote the story, my first bit of crime fiction, on request. The character was Wylie Melville, a therapist and police consultant; the story was “The Timing of Unfelt Smiles,” and it appeared in Miami Noir and in Best American Mystery Stories 2007. I wanted to give Wylie a much larger problem to solve and to put his life in great danger. That’s what got me started, that and the long legacy of police and political corruption in South Florida, rich material to work with. Then, having done it once, I thought, I’ll do it again. I liked Wiley and Bay and wondered what mayhem would follow them and where would they go. They went to Vegas so that Bay could ply his trade at the poker tables. To be honest, I hadn’t read much crime fiction before I wrote crime fiction. Sherlock Holmes, of course, books my friends Les Standiford, James W. Hall, and Dennis Lehane wrote. So if I broke any rules, I may not have known what they were. I wrote the two novels like I wrote every book with the focus on characters and themes, not on plot. This is what it means to be a human being and this is how it feels.

TBD: What do you want people to take away from your novel?

JD: Before I was a writer, and before I was a house painter, I worked for a while in social service organizations, a suicide prevention hotline, like the one Wylie works at in Vegas, a youth center, a drug prevention program. So I was in touch with that difficult life that so many people have here. In America. I worked with so many people who had lost hope and others who were in terrible emotional pain. And I’ve never lost that feeling that we don’t do enough to take care of the less fortunate. The exploitation and oppression of unfortunate people is something I’d hope the reader would think about. Daily violence is a norm here, but it’s easy to look the other way. And I want the reader to care about Wylie and his friends.

TBD: What were some of the pleasures and perils of writing this book?

JD: I spoke glibly above saying how theme and character drove the novel. Plot’s always been the most difficult aspect of novel writing for me. It’s so damn hard. So when I wrote the first Coyote novel, I got to about 250 pages when I realized I didn’t know who committed those murders in the opening chapter, and I thought, this is why the crime writers make the big money: they have to write a novel and solve a crime. Too late then to bring a bad guy with a gun onto the stage. So it was pack to page one. Same thing this time. As possible suspects entered the novel, I paid attention and watched them looking for clues. Anyone of them could have done the deed, but who really did? Wylie’s no Sherlock Holmes, no consulting detective, but he is a man who pays attention. And he doesn’t work alone. He has the illusionist Bay and the bedlamite Open Mike by his side.

TBD: Tell us about how you got your first book published?

JD: It was a book of short stories, and I had probably published six or seven stories in literary journals. I had a bunch of others, and I put them together as a book, and I went through one of those books Writer’s Digest put out or something like that. And I looked through all of the agents looking for short story collections, and there were three.

TBD: I’m surprised there were three!

JD: I know, I know! So I wrote to the three of them, and one of them got back to me. He was very enthusiastic. I would tell anybody who is looking for an agent, make sure the agent is excited about you and your project. Not just, “I’ll do it…” Because it’s hard for an agent to sell a book. Especially if it’s short stories. So my agent sent my book of stories around for about a year. It finally sold to Jill Bialosky at Norton, and I’ve been with Jill and Norton ever since. I remember my editor saying, “You’re the last guy I’ll ever sell a book of stories for.”

TBD: Your career is interesting and highly unusual for today in terms of sticking with one publisher for each book. And it’s a publisher that’s independent but has real chops in this business. Not to mention the fact that you write very quirky books that are not highly commercial, mainstream, etcetera. How can other writers achieve this kind of elusive success?

JD: First of all, the best readers you’re going to get are your agent and your editor. They’re generous. They want your book to succeed. And they know what they’re talking about. Even if you disagree with them, I always say, just do what they tell you to do. Because they know the business. I don’t know anything about the business. I don’t want to know; I want to write. I also say, if you write something beautiful and moving and telling, it’ll get published. But it may not get published when you want it to be, or where you want it to be. The important thing for a lot of young writers is getting it published. I steer them away from self-publishing. Some of them have, and that’s alright. But you want to get the imprimatur of somebody else. Somebody else who believes in you. Small presses are as good a place to be published as large presses… I mean obviously you’re not getting the same money. But the money isn’t like it was before. You used to be sent on book tours. Now you’re lucky if they give you lunch money. The important thing is to get yourself into the game. You get your book around. You have people reading it. Just don’t give up. You owe it to your characters that you love to get other people to read about them. Until you get an agent, you’re going to do the business work too, and persist with it. I think in some ways publishing is more democratic than it ever was.

TBD: When we go to these conferences, there’s always one person who’s telling writers, “You have to be on Facebook! You have to be on Twitter! You have to have a website, blah blah blah-” And you can see the blood draining out of writers’ faces.

JD: The publishers want you to do work with them, which I understand. When I did my first book of stories, I set up what I called the Motel Six tour. I told them, “Get me the books and a bookstore, and I’ll drive. I’ll take my wife and my kid, and we’ll drive to all the bookstores.” And that’s what I did. And they were all really happy, because this was before social media. I printed up a fake newspaper from Louisiana Power and Light, and Norton sent it around, and got hard copies to people. It was fun. They appreciated that I was willing to do it. I still do it. Somebody just asked me to do a bookstore in Baltimore. But I’m thinking, “How much is this going to cost me?” In the old days, they put me up in beautiful hotels. Paid for everything. Now, at least for mid-list people like me, it’s not happening. And I don’t think it’s happening too much in general anymore. I also have gotten on Facebook because Norton said to do that. A guy helped me out. My wife is good at the computer. I think that’s been kind of helpful. It’s a nice way to spread the news. I saw there was a good review of my new book in the Tampa Bay paper on Sunday, and I put it online. Lots of people have liked it already. They know about the book, they buy the book. Twitter I’ve never been on. I remember once, Carol Houck Smith (who was an editor at Norton for years) and I were sitting together by these editors, and they were all answering questions with, “You need a platform.” And Carol muttered under her breath, “I don’t need a goddamn platform, I need a great book!”

TBD: What are you reading now?

JD: I tend to read a lot of books at the same time. I’m reading Lee Martin’s new novel Late One Night, which begins with the death of a mother and three kids in a fire that may or may not have been arson. And I started Campbell McGrath’s new poetry collection, XX, in which he writes a poem for every year in the last century, in the voices of some of the century’s prominent figures, like Picasso. Mao, and Elvis. Also reading Wired to Create, by Kaufman and Gregoire, and Actual Minds, Possible Worlds by Jerome Bruner. I’m loving, if not completely understanding, Lawrence M. Krauss’s A Universe from Nothing and Carlo Rovelli’s Seven Brief Lessons on Physics.

TBD: How does teaching fiction help or hinder you as a fiction writer?

JD: It only helps. Every reading and every discussion of a story helps me see how stories work or don’t work, including my own. We’re all apprentices in a craft where no one is a master–I think Hemingway said that. This is the craft so long to learn. I always feel better at the end of class than at the start. I always feel like rushing home (which is actually impossible on Biscayne Boulevard) and getting back at whatever it is I’m writing. To be honest, there are moments that I would rather be learning about my central character’s secrets than reading a story about goblins with swords, but I know I’ll learn something about setting a scene, let’s say, in the goblin story that will be valuable to my students and to me.

TBD: We hate to ask you this, but since you actually wrote a book about how to write a novel, we feel we have to. What advice do you have for writers?

JD: Probably the advice you were expecting to hear: read and write every day. No holidays for the writer. We always find time to do the things we love. We only have to want to write as much as we want to go to the movies. And if you don’t love writing and reading, do something else. It’s too hard, and discipline won’t bring you to the writing desk. Only love for stories will do that. Here’s Faulkner on reading: “Read, read, read. Read everything — trash, classics, good and bad, and see how they do it. Just like a carpenter who works as an apprentice and studies the master. Read! You’ll absorb it.” And Chekhov on writing: “Write as much as you can! Write, write, write till your fingers break.”

John Dufresne is the author of seven novels, including I Don’t Like Where This is Going and No Regrets, Coyote. Among other honors, he has received a Guggenheim Fellowship and is a professor in the MFA program at Florida International University. He lives in Dania Beach, Florida. For more information, please visit www.johndufresne.com.

John will be joining our Pitchapalooza panel in Miami on May 7, 2016, at 2 p.m. Learn more at the Miami Herald.